The State of Cancer Disparities in the United States, 2023

An ACS report on racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in cancer occurrence, programs that target cancer disparities, and policy recommendations.

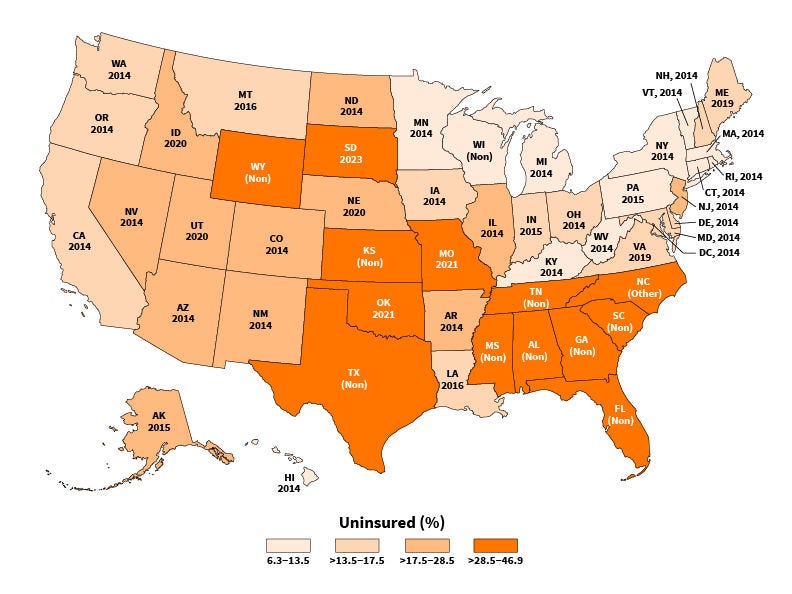

- Map

- Text Alternative

Proportion of People by State, Age 19 to 64, with Incomes Below the Federal Poverty Level and Without Health Insurance

The states in dark orange on this 2021 US map have the highest percentage of people who have low income and who lack health insurance, and the numbers below the state abbreviations show the year that Medicaid Expansion was approved. States that did not expand Medicaid–nonexpansion states—are labelled (Non). The orange shade is lighter on states with a smaller percentage of people without health insurance. Source: “American Cancer Society’s report on the status of cancer disparities in the United States, 2023”

Proportion of People by State, Age 19 to 64, with Incomes Below the Federal Poverty Level and Without Health Insurance

This 2021 map of the United States shows the percentage of people in each state with a yearly income that is below the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) and who don’t have health insurance coverage. It also lists the year that each state implemented Medicaid Expansion.

States that have not expanded Medicaid or who expanded Medicaid in 2021 or after were more likely to have higher percentages of uninsured people with low incomes.

States that expanded Medicaid before 2021 were more likely to have lower percentages of uninsured people with low incomes.

States with more than 28.5% to 46.9% uninsured people with low incomes

Alabama (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Florida (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Georgia (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Kansas (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Mississippi (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Missouri (2021)

North Carolina (adopted Medicaid expansion but hadn’t implemented yet in 2023)

Oklahoma (2021)

South Carolina (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

South Dakota (2023)

Tennessee (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Texas (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

Wyoming (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

States with more than 17.5% to 28.5% uninsured people with low incomes

Alaska (2015)

Arizona (2014)

Arkansas (2014)

Colorado (2014)

Idaho (2020)

Illinois (2014)

Nebraska (2020)

Nevada (2014)

New Jersey (2014)

New Mexico (2014)

North Dakota (2014)

Utah (2020)

States with more than 13.5% to 17.5% uninsured people with low incomes

California (2014)

Delaware (2014)

Indianna (2015)

Iowa (2014)

Louisianna (2016)

Maine (2019)

Maryland (2014)

Montana (2016)

New Hampshire (2014)

Ohio (2014)

Oregon (2014)

Virginia (2019)

Washington (2014)

Washington DC (2014)

States with 6.3% to 13.5% uninsured people with low incomes

Connecticut (2014)

Hawaii (2014)

Kentucky (2014)

Massachusetts (2014)

Michigan (2014)

Minnesota (2014)

New York (2014)

Rhode Island (2014)

Vermont (2014)

West Virginia (2014)

Wisconsin (Medicaid nonexpansive state)

The Challenge

Over the past several decades, there has been progress in cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment in the United States. And that's lead to overall declines in cancer death rates. Yet, people of color, with lower socioeconomic status and education levels, or who live in rural areas have not benefited equitably from these advances. The main reason is racism and discrimination along with other social determinants of health that lead to both social inequities and discriminatory policies. Together, they are significant root causes of health disparities.

These disparities in cancer outcomes based on race, income, education, and geography will likely widen without attention from health policymakers and health care providers.

Glossary for Nonscientists

Featured Term:

Social Determinants of Health

A mix of conditions of daily life—where people live, work, learn, play, worship, and age—influenced by a broad set of forces and systems that shape those conditions, including social norms, social policies, political systems, and economic policies and climate.

Social determinants of health can positively or negatively affect the occurrence of cancer because of their effects on educational and job opportunities, income, insurance coverage, housing, transportation, public safety, food security, social inclusion and non-discrimination, and access to affordable health services of high quality.

Structural racism and discrimination are examples of long-lived social determinants of health that result in social inequities and discriminatory policies.

The Research

Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, is the senior scientific director of Cancer Disparity Research in Surveillance & Health Equity Science at the American Cancer Society (ACS). He and his team updated an analysis of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in cancer occurrence in the US from 2016 through 2020. They looked at differences in exposure to risk factors for developing cancer, access to utilization of preventive cancer care and cancer screening, cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, survival, and mortality.

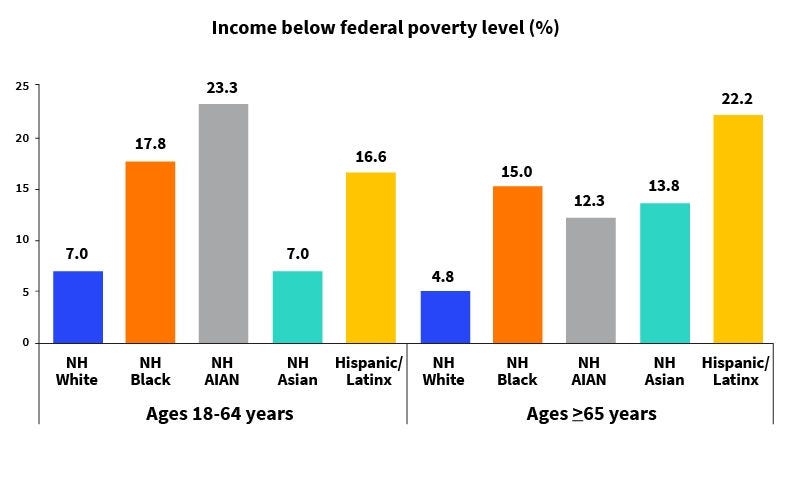

- Chart

- Text Alternative

Percentages of People by Race/Ethnicity With Income Below the Federal Poverty Level

This bar chart shows how far (by percentage) each race is below the federal poverty level for two age groups—for ages 18 to 64 on the left, and ages 65 and older after the separation line on the right. Source: “American Cancer Society’s report on the status of cancer disparities in the United States, 2023”

Percentages of People by Race/Ethnicity With Income Below the Federal Poverty Level

This bar chart shows how far (by percentage) each race is below the federal poverty level for two age groups—for ages 18 to 64 and ages 65 and older.

Ages 18 to 64

Non-Hispanic (NH) White 7%

Non-Hispanic (NH) Black 17.8%

Non-Hispanic (NH) AIAN 23.3 %

Non-Hispanic (NH) Asian 7%

Hispanic/Latinx 16.6%

Ages 65 and Older

Non-Hispanic (NH) White 4.8%

Non-Hispanic (NH) Black 15%

Non-Hispanic (NH) AIAN 12.3 %

Non-Hispanic (NH) Asian 13.8%

Hispanic/Latinx 22.2%

Here are some of their findings:

Cancer Incidence Rate Disparities

- Lowest incidence rates for all major cancer types: Asian Pacific Islanders (API), except for lung cancer and female breast cancer. For those 2 types of cancer, Hispanic populations had the lowest incidence rates.

Hispanic populations had lower incidence rates than White populations (and higher than API populations) for all cancers combined, prostate, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers.

- Highest incidence rates for all major cancer types: Black people, except for all cancers combined and both breast and lung cancer in women, which were higher for White populations. Cervical cancer was higher in American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and Hispanic women compared to both Black and White women.

- Higher cancer incidence rates for nonmetropolitan/rural populations: Compared with metropolitan areas (cities with a population of 1 million or more), people living in nonmetropolitan/rural areas have higher overall cancer incidence rates, and specifically higher for lung, cervical, and colorectal cancer.

- Lower cancer incidence rates for nonmetropolitan/rural populations: Compared with metropolitan areas, people living in nonmetropolitan/rural areas have a lower incidence of breast and prostate cancer.

- People younger than age 65 had more disparities in cancer incidence in nonmetropolitan areas among both males and females and across all racial/ethnic groups studied except for cervical cancer in Black women, where the greater disparity was in those 65 and older.

Despite some progress in recent decades, cancer disparities are still a major issue in the United States, and they may further widen because of increasing costs of novel treatments and advanced medical technologies. Much more work needs to be done to enhance health equity and mitigate cancer disparities."

Farhad Islami, MD, PhD

Senior Scientific Director, Cancer Disparity Research

Surveillance and Health Equity Science, American Cancer Society

Cancer Death Rate Disparities

Lowest death rates for all major cancer types: API and Hispanic populations for both men and women

Highest death rates for all major cancer types: AIAN and Black populations for both men and women

Highest cancer death rates for nonmetropolitan/rural populations: All cancer types, including breast and prostate cancer even though they had lower incidence rates in rural regions. Differences were greater in people younger than age 65.

Black and White people age 25 to 74 with 12 or less years of education: 2 to 3 times higher risk of dying from cancer overall compared with people the same age with 16 or more years of education, with the difference widening as years of education increased. The risk of dying from lung cancer was 4 to 6 times higher.

How ACS Is Working to Reduce Diversity

“The State of Cancer Disparities in the United States” report also shared information about Federal, state, and local policies and programs to decrease disparities and ACS programs and resources targeting cancer disparities, including:

- Cancer Facts & Figures for African American/Black People

- Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latino People

- VOICES of Black Women, a new cohort study of Black women age 25 to 55 in the US

3 Programs to enhance cancer research and career development:

- The Summer Healthcare Experience (SHE) in Oncology to introduce female high school students to cancer research and oncology care

- The ACS Diversity in Cancer Research (DICR) Internship Program for undergraduate college students to have a mentored experience in cancer research

- Post-Baccalaureates (PBs) Fellows Program for recent college graduates planning to pursue a doctoral degree to earn a 2-year preparatory cancer research certificate

- Research grants to increase diversity in cancer clinical trials and development of Cancer Health Equity Research Centers (CHERCs).

Suggested Actions for all Cancer Experts

Islami and other research authors proposed that federal and state governments, health and cancer care systems, cancer advocacy organizations including the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), and others, work together to reduce cancer disparities by taking actions such as these:

- Increase health insurance coverage for people with lower incomes: Expand Medicaid access and make expanded Marketplace subsidies permanent.

- Cut costs: Address high out-of-pocket costs for cancer treatment.

- Focus on tobacco use: Implement and enforce tobacco cessation programs and policies and advocate for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to use its full authority to regulate tobacco products and prohibit all flavored products, including menthol. (Black people have historically been targeted by the tobacco industry to encourage their use of menthol cigarettes.)

- Make cancer screening more comprehensive: Increase funding for cancer screening programs, including the National Breast and Cervical Early Detection Program, ensure coverage of biomarker testing, and support access to early detection tests that check for multiple cancers.

- Reduce the risk for personal financial toxicity: Ensure paid leave for working people with cancer, survivors, and caregivers.

Why It Matters