Managing Female Sexual Problems Related to Cancer

Sex, sexuality, and intimacy are just as important for people with cancer as they are for people who don’t have cancer. In fact, sexuality and intimacy have been shown to help people face cancer by helping them deal with feelings of distress, and when going through treatment. But, the reality is that a person's sex organs, sexual desire (sex drive or libido), sexual function, well-being, and body image can be affected by having cancer and cancer treatment. How a person shows sexuality can also be affected. Read more in How Cancer and Cancer Treatment Can Affect Sexuality.

Managing sexual problems is important, but might involve several different therapies, treatments, or devices, or a combination of them. Counseling can also be helpful. The information below describes ways to approach some of the more common sexual problems an adult female with cancer may experience. If you are a transgender person, please talk to your cancer care team about any needs that are not addressed here.

Ask about possible changes in sexuality from treatment

It’s very important to talk about what to expect, and continue to talk about what's changing or has changed in your sexual life as you go through procedures, treatments, and follow-up care. Don't assume your doctor or nurse will ask about any concerns you have about sexuality. Remember, if they don't know about a problem you're having, they can't help you manage it. Here are some ways you can start talks with your cancer care team about the problems you might be having.

Know when to ask questions

The best time to talk with your doctor or cancer team about possible side effects or long-term changes in your sex life is before treatment. If this isn't possible, or you don't think about asking these kinds of questions before surgery or treatment, you can start to talk with them shortly after surgery or when treatment starts. But you can bring up the subject any time during and after treatment, too.

Ask the right questions

It’s important to know what to expect. When you're asking questions before surgery or treatment, here are some that can open the door to more questions and follow-up:

- Will my surgery affect my sex life? If so, what can I expect?

- Will my treatment (radiation, chemo, hormone therapy, etc) affect my sex life? If so, what can I expect?

- Will the effects last a short time, a long time, or be permanent?

- What can be done about these effects? Is there a cost to what can be done?

- Can I see a specialist or counselor?

- Are there any other treatments that are just as effective for my cancer but have different side effects?

- Do you have any materials I can read or where do you recommend I find more information?

Maybe you've already had surgery or started treatment, but didn't ask questions (or get enough information) beforehand. Maybe you've read some things on the internet or heard about someone else's experience with the same type of cancer you have. Maybe you're able to think more clearly now than when you were first diagnosed and realize you have questions. Whatever the reason, if you wondering about something, ask! Here are some ways to start talking with your cancer care team:

- "I was reading about (surgery/treatment) and that it might cause sexual problems. Can you explain that to me?"

- "I know someone who went through this same thing and heard about problems they had with sex. Can you give me more information about this?"

- "I notice a change in how I feel about sex/when I'm having sex. Can you talk to me about this? Is this normal and what can I do?"

- "I am having trouble adjusting to some changes in my body. What can I do?"

Managing common sexual problems in adult females with cancer

Premature (early) menopause

Depending on the stage in life, type of cancer, and type of surgery and treatment needed, some women are at an increased risk for reduced hormones. If the woman has already gone through the "change of life" (menopause), the chance of having these symptoms might not be as high. But some women have surgery or treatment that brings on these hormone changes before they would naturally happen, and this is called premature menopause. This causes monthly hormone cycles to slow or stop, meaning monthly periods (menstruation) stop. It's also known as amenorrhea.

It's important to know how surgery and treatment might affect your cycles and hormones. This is important for all women so they know the symptoms to expect. But it's especially important for younger women because of the possibility of pregnancy if cycles do not completely end or if hormones are not permanently affected. Ask your cancer care team about your specific situation.

- Surgeries that can lead to premature menopause include removal of the ovaries or a total hysterectomy (removal of the ovaries is included in this procedure). These surgeries cause menopause to be permanent.

- For women who still have their ovaries, including those who are still having periods, certain types of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy can lead to ovarian failure which causes premature menopause. Sometimes this menopause can be temporary, but many times it is permanent.

If you can expect to go through premature menopause, or have gone through it because of cancer surgery or treatment, you may be bothered by frequent hot flashes and other symptoms.

- Hot flashes, or flushes, can happen throughout the day but can be especially bothersome at night. They may include other symptoms, such as chills, flushing (redness and warm) on the face, anxiety, and feeling like your heart is racing. You can learn more about hot flashes and how to manage them in Hot Flashes.

- Some women may have lower sexual desire, which can be affected by menopause symptoms as well as by stress and poor sleep.

- Hormone changes can also cause vaginal pain and dryness, and thinning of vaginal tissues.

Female hormones (estrogen and/or progesterone) in a pill or patch can help with menopause symptoms. But, some women may not be able to take hormones because of the type of cancer they have. Sometimes these hormones are not recommended because they can promote certain types of cancer growth in female organs. They can cause other health problems, too.

If you have questions or concerns about hormone therapy, talk with your cancer care team about the risks and benefits as they apply to you. If you and your provider decide that hormone therapy is the best treatment for you, be sure you understand the correct dose to use, when to use it, and when to expect it to take effect. Sometimes doses need to be changed to get the best effect. However, it’s important that doses are monitored and that you have regular check-ups.

Vaginal dryness and atrophy

Vaginal fluids and moisture are important for sexual function, and can make gynecologic exams more comfortable. As women age, the vagina can naturally lose moisture and elasticity (the ability to stretch or move comfortably). Cancer surgeries and treatments can speed up these changes. Vaginal dryness and atrophy can make intercourse difficult, and sometimes painful. As with hot flashes, taking hormones can help. But, sometimes these hormones are not recommended because they can promote certain types of cancer growth in female organs.

Lubricants

Fluids increase in your vagina when you are excited. If you have vaginal dryness, you may need extra lubrication to make sex comfortable. If you use a vaginal lubricant, it's best to choose a water-based gel that has no perfumes, coloring, spermicide, herbal remedies, or flavors added, as these chemicals can irritate your delicate genital tissues. Also, warming gels can cause burning in some people. Lubricants can usually be found near the birth control or feminine hygiene products in drug stores or grocery stores. Be sure to read the labels, and talk with a nurse, doctor, or pharmacist if you have questions.

Petroleum jelly, skin lotions, and other oil-based lubricants are not good choices for vaginal lubrication. In some women, they may raise the risk of yeast infection. And if latex condoms are used, they can be damaged by petroleum products and lotions. Also, watch out for condoms or gels that contain nonoxynol-9 (N-9). N-9 is a birth control agent that kills sperm, but it can irritate the vagina, especially if the tissues are already dry or fragile.

Before sex, put some lubricant around and inside the entrance of your vagina. Then spread some of it on your partner’s penis, fingers, or other insert. This helps get the lubricant inside your vagina. Many couples treat this as a part of foreplay. If vaginal penetration lasts more than a few minutes, you may need to stop briefly and use more lubricant. Even if you use vaginal moisturizers every few days, it’s best to use gel lubricant before and during sex.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to help keep your vagina moist and at a more normal acid balance (pH) for a few days. Vaginal moisturizers are applied at bedtime for the best absorption. It’s not uncommon for women who’ve had cancer to need to use moisturizers several times per week. Vaginal moisturizers are different than lubricants – they last longer and are not usually used for sexual activity.

Vaginal estrogens

Vaginal estrogen therapy is a treatment option for vaginal atrophy (when the vaginal walls get thinner and less stretchy) for some women. But, some women may not be able to take hormones because of the type of cancer they have. Sometimes these hormones are not recommended because the estrogens can promote certain types of cancer growth in female organs.

Vaginal hormones are applied to and absorbed into the genital area. They come in gel, cream, suppository, ring, and tablet forms. Most are put into the vagina, although some creams can be applied to the vulva (outer part of the vagina). They focus small amounts of hormones on the vagina and nearby tissues, so that very little gets in the bloodstream to affect other parts of the body. Local vaginal hormones need a prescription.

Reaching orgasm after cancer treatment

Usually, women who could reach orgasm before cancer treatment can do so after treatment. But some women may have problems with this.

Here are a few ideas that might help.

- Having a sexual fantasy before or during sex. A fantasy can be a memory of a past experience or a daydream about something you’ve never tried. A strongly sexual thought can distract you from negative thoughts and fears about performing.

- Using a hand-held vibrator for extra stimulation. Hold it yourself, or ask your partner to caress your genitals with it. You can steer your partner to the areas that respond best and away from those that are tender or uncomfortable.

- Changing the position of your legs during sexual activity. Some women reach orgasm more easily with their legs open and thigh muscles tense. Others prefer to press their thighs together.

- Tighten and relax your vaginal muscles in rhythm during sex or while your clitoris is being stroked. Or, tighten and relax the muscles in time with your breathing. This helps you focus on what you’re feeling. Contract your vaginal muscles and pull them inward as you inhale, and let them relax loosely as you exhale.

- Asking your partner to gently touch your breasts and genital area at the same time or separately. Experiment with your partner to find the type of touch that most excites you.

You also can talk with your cancer care team and gynecologist for referral for counseling and sex therapy that can be helpful.

Pain during sex

Genital pain

For women who have vaginal dryness or atrophy, sex may be painful. This is called dyspareunia. Pain may be felt in the vagina itself or in the tissues around it, like the bladder and rectum. After certain surgeries and radiation to the pelvis or genital area, the vagina is sometimes shorter and narrower. But hormone changes are the most common cause of vaginal pain after cancer treatment. If you don’t produce enough natural lubricant or moisture to make your vagina slippery, sex can be painful. It can cause a burning feeling or soreness. The risk of repeated urinary tract infections or irritation also increases when there is vaginal irritation during sex.

If you have genital pain during sex:

- Tell your cancer care team or gynecologist about the pain. Do not let embarrassment keep you from getting medical care.

- Make sure your partner knows the pain may not be as bad if you feel very aroused before you start vaginal sex. Your vagina expands to its fullest length and width only when you are highly excited. This is also when the walls of the vagina produce lubricating fluid. It may take a longer time and more touching to get fully aroused.

- Use water-based lubricating gel around and in your vagina before vaginal penetration. You can also use lubrication suppositories (soft gel pellets) that melt during foreplay.

- Let your partner know if any types of touching cause pain. Show your partner ways to caress you or positions that don’t hurt. Usually, light touching around the clitoris and the entrance to the vagina won’t hurt, especially if the area is well-lubricated.

- For vaginal sex, try a position that lets you control the movement. Then, if deep penetration hurts, you can make the thrusts less deep. You can also control the speed.

- Learning to be aware of pelvic muscles and how to control them is important in understanding and managing vaginal pain. Once a woman has felt pain during sex, she often becomes tense in sexual situations. Without knowing it, she may tighten the muscles just inside the entrance of the vagina. This makes vaginal penetration even more painful. Sometimes she clenches her muscles so tightly that her partner cannot even enter her vagina. You can become aware of your vaginal muscles and learn to relax them during vaginal penetration. Exercises that teach control of the pelvic floor and vaginal muscles are called Kegels

- Your doctor may be able to refer you to a special therapist for pelvic physical therapy or pelvic rehabilitation. This therapy might help you relax your vaginal muscles and help you manage pain during sex.

Non-genital pain

Other types of pain that are not in your genital area can affect how comfortable you are during sex. If you’re having pain other than in your genital area, these tips may help lessen it during sex. You might need to plan sexual activity rather than be spontaneous for some of these to help.

- If you’re using pain medicine, take it an hour or so before having sex so it will be working when you’re ready.

- Find a position that puts as little pressure as possible on the sore areas of your body. If it helps, support the sore area and limit its movement with pillows. If a certain motion is painful, choose a position that doesn’t require it or ask your partner to take over the movements during sex. You can guide your partner on what you would like and what makes you most comfortable.

- Focus on your feelings of pleasure and excitement. With this focus, sometimes the pain lessens or fades into the background.

Vaginal dilator

A vaginal dilator is a plastic or rubber tube used to enlarge or stretch (dilate) the vagina. Dilators also help women learn to relax the vaginal muscles if they are used with Kegel exercises. They come in many forms and are often used after radiation to the pelvis, cervix, or vagina. Even if a woman isn’t interested in staying sexually active, keeping her vagina normal in size allows more comfortable gynecologic exams.

If it's needed, your doctor or nurse will tell you where to buy a dilator. Check with your insurance company, too, and find out if you need a prescription. You will also be taught when to start using it, and how and when to use it. The dilator feels much like putting in a large tampon for a few minutes. It can be used several times a week to keep your vagina from getting tight from scar tissue that may develop.

Special aspects of some cancer treatments

Breast surgery

Surgery for breast cancer might not directly affect sexual function and doesn't directly affect intercourse. However, it can have an impact on body image. And, sensation when being touched during sex can be reduced in the area that's affected by breast surgery.

- Breast-conserving surgery (also called a lumpectomy, quadrantectomy, partial mastectomy, or segmental mastectomy) is a surgery in which only the part of the breast containing the cancer is removed. The goal is to remove the cancer as well as some surrounding normal tissue. How much breast is removed depends on where and how big the tumor is, as well as other factors.

- Mastectomy is a surgery in which the entire breast is removed, including all of the breast tissue and sometimes other nearby tissues. There are several different types of mastectomies. Some women may have a double mastectomy, in which both breasts are removed.

Managing the physical and psychological effects of having breast surgery is important. Many woman having surgery for breast cancer might have and choose the option of breast reconstruction. This can include nipple reconstruction too, and tattooing for the nipple and surrounding area. Counseling and support groups may be helpful too. Some women feel more comfortable and have a better self-image with these options, but they often require multiple procedures. Read more in Breast Reconstruction Surgery and talk to your cancer care team, surgeon, and gynecologist about what is best for your situation.

Urostomy, colostomy, or iIeostomy

An ostomy is a surgical opening created to help with a body function. The opening itself is called a stoma.

- A urostomy takes urine through a new passage and sends it out through a stoma on the abdomen (belly).

- A colostomy and ileostomy are both stomas on the belly for getting rid of body waste (stool). In an ileostomy, the opening is made with the part of the small intestine called the ileum. A colostomy is made with a part of large intestine called the colon.

There are ways to reduce the effect of ostomies on your sex life. One way is to be sure the appliance (pouch system) fits well. Check the seal and empty your pouch before sex. This will reduce the chance of a leak. Learn more in Ostomies.

Tracheostomy and laryngectomy

A tracheostomy is a surgery that removes the windpipe (trachea). It can be temporary or permanent, and you breathe through a stoma (opening or hole) in your neck.

Laryngectomy is surgery that removes the voice box (larynx). It leaves you unable to talk in the normal way, and since the larynx is next to the windpipe that connects the mouth to the lungs, you breathe through a stoma (hole) in your neck.

A scarf, necklace, or turtleneck can look good and hide the stoma cover.

During sex, a partner may be startled at first by breath that hits at a strange spot. You can lessen odors from the stoma by avoiding garlic or spicy foods and by wearing perfume.

Sometimes problems in speaking can make it hard for couples to communicate during sex. If you’ve learned to speak using your esophagus, talking during sex is not a big problem. A speech aid or electronic voice box built into the stoma might also work well.

Treatment for head and neck cancer

Some cancers of the head and neck are treated by removing part of the bone structure of the face. This can change your appearance. Surgery on the jaw, palate, or tongue can also change the way you look and talk. Facial reconstruction might help regain a more normal look and clearer speech.

Limb amputation

Treatment for some cancers can include surgically removing (amputating) a limb, such as an arm or leg. A patient who has lost an arm or leg may wonder whether to wear the artificial limb (prosthesis) during sex. Sometimes the prosthesis helps with positioning and ease of movement.

Feeling good about yourself and feeling good about sex

Sometimes friends and lovers withdraw emotionally from a person with cancer. Don’t give up on each other. It may take time and effort, but keep in mind that sexual touching between a woman and her partner is always possible. It may be easy to forget this, especially if you’re both feeling down or haven’t had sex for a while. See "Keep talking and work together to manage problems" in Cancer, Sex, and the Female Body for some tips to help you and your partner through this time. And keep in mind that you may need extra help with the changes caused by cancer that can turn your and your partner’s lives upside down.

Changes in the way you look

Cancer surgery and treatment can affect your appearance. Surgical scars may be visible. Women with breast cancer may lose a breast. Hair loss can occur with some treatments, including hair on your head, and possibly eyebrows, eyelashes, and pubic hair, too. You may also gain or lose weight, and muscle mass may be affected by the activity you can and can't do, or if you have trouble eating. Certain treatments can cause skin rash and changes. Your nails may be affected, too.Caring for Your Appearance Read more in .

Feeling good about yourself begins with focusing on your positive features. Talk to your cancer care team about things that can be done to limit the damage cancer can do to the way you look, your energy, and your sense of well-being. When you’re going through cancer treatment, you can feel more attractive by disguising the changes cancer has made and drawing attention to your best points.

What do you see when you look at yourself in the mirror? Some people notice only what they dislike about their looks. This mirror exercise can help you adjust to body changes:

- Find a time when you have privacy for at least 15 minutes. Be sure to take enough time to really think about how you look. Study yourself for that whole time, using the largest mirror you have. What parts of your body do you look at most? What do you avoid seeing? Do you catch yourself having negative thoughts about the way you look? What are your best features? Has cancer or its treatment changed the way you look?

- First, try the mirror exercise when dressed. If you normally wear clothing or special accessories to disguise changes from treatment, wear them during the mirror exercise. Practice this 2 or 3 times, or until you can look in the mirror and see at least 3 positive things about your looks.

- Once you’re comfortable seeing yourself as a stranger might see you, try the mirror exercise when dressed as you would like to look for your partner. If you’ve had an ostomy, for example, wear a bathrobe or teddy you like. Look at yourself for a few minutes, repeating the steps in the first mirror exercise. What’s most attractive and sexy about you? Give yourself at least 3 compliments on how you look.

- Finally, try the mirror exercise in the nude, without disguising any changes made by the cancer. If you have trouble looking at a scar, bare scalp, or an ostomy, take enough time to get used to looking at the area. Most changes are not nearly as ugly as they seem at first. If you feel tense while looking at yourself, take a deep breath and try to let all your muscles relax as you exhale. Don’t stop the exercise until you have found 3 positive features, or at least remember the 3 compliments you paid yourself before.

The mirror exercise may also help you feel more relaxed when your partner looks at you. Ask your partner to tell you some of the things that are enjoyable about the way you look or feel to the touch. Explain that these positive responses will help you feel better about yourself. Remember them when you’re feeling unsure.

Dealing with negative thoughts

Working on what you think about can help make a sexual experience better. Try to become more aware of what you tell yourself about how attractive or sensual you feel. There are ways to help turn negative thoughts around. For example:

- Write down 3 negative thoughts you have most often about yourself as a sexual person.

- Now write down a positive thought to counter each negative thought. For example, if you said, “No one wants a woman with a urostomy,” you could say to yourself, “I can wear a lacy ostomy cover during sex. If someone can’t accept me as a lover with an ostomy, then they’re not the right person for me.” The next time you are in a sexual situation, use your positive thoughts to override the negative ones you usually have.

- If you have a favorite feature, this is a good time to indulge yourself a little and play it up.

- If negative thoughts intrude and you find yourself overwhelmed or discouraged, you may want to talk with your cancer care team about working with a mental health professional.

Depression is common during and after cancer treatment and has a huge effect on your life, including your thoughts, relationships, and overall well-being. If you lack interest in things you usually enjoy or are unable to feel pleasure and happiness, please talk to your cancer care team.

Overcoming anxiety about sex

Sometimes because of a cancer-related symptom or treatment side effect, it might not be possible to be as spontaneous as you were in the past. The most important thing is to open up the topic for discussion and begin scheduling some relaxed time together.

Self-stimulation (or masturbation) is not a required step in restarting your sex life, but it can be helpful. It can also help you find out where you might be tender or sore, so that you can let your partner know what to avoid.

Sexual activity with your partner

Just as you learned to enjoy sex when you started having sex, you can learn how to feel pleasure during and after cancer treatment.

Depending on your situation, you may feel a little shy. It might be hard to let your partner know you would like to be physically close, so be as clear and direct as you can.

Making sex more comfortable

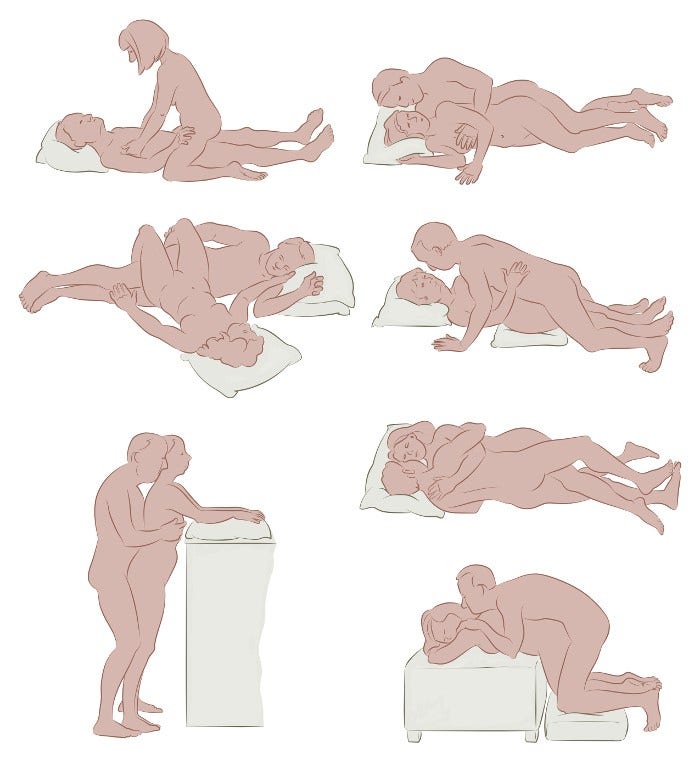

If you still have some pain or feel weak from cancer treatment, you might want to try new positions. Many couples have found one favorite position, particularly for vaginal penetration, and rarely try another. Talk to your partner and learn different ways to enjoy sex that are most comfortable. The drawings below are some ideas for positions that may help in resuming sex.

There's no one position that's right for everyone. You and your partner can work together to find what’s best for you. Pillows can help as supports. Keeping a sense of humor can always lighten up the mood.

- Written by

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Practice bulletin no. 213: Female sexual dysfunction. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;134:e1-18.

Carter et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(5):492-513.

Faubion SS, Rullo JE. Sexual dysfunction in women: A practical approach. American Family Physician. 2015;92(4):281-288.

Katz A. Breaking the Silence on Cancer and Sexuality: A Handbook for Healthcare Providers. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society.; 2018.

Katz, A. Woman Cancer Sex. Pittsburgh: Hygeia Media, 2010.

Mitchell K, Wellings K, Graham C. How do men and women define sexual desire and sexual arousal? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2012;40(1). 10.1080/0092623X.2012.697536.

Moment A. Sexuality, intimacy, and cancer. In Abrahm JL, ed. A Physician’s Guide to Pain and Symptom Management in Cancer Patients. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014:390-426.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Survivorship [Version 2.2019]. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf on January 31, 2020.

Nishimoto PW, Mark DD. Sexuality and reproductive issues. In Brown CG, ed. A Guide to Oncology Symptom Management. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2015:551-597.

Zhou ES, Bober SL. Sexual problems. In DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, eds. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019:2220-2229.

Last Revised: February 5, 2020

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.