Your gift is 100% tax deductible

How Cancer and Cancer Treatment Can Affect Fertility in Women

Some cancers and cancer treatments can cause changes in your body that affect your fertility (your ability to have children). This could include hormone changes or damage to certain parts of your body.

Learn more about how cancer and its treatment can affect fertility in women and how to find help with fertility issues.

- What is fertility?

- What is infertility?

- Talking to your cancer care team about fertility

- What causes fertility problems in women with cancer?

- Who is more (or less) likely to have fertility problems?

- Avoiding pregnancy during cancer treatment

- How cancer treatment affects fertility

- Evaluating menstruation and fertility after cancer treatment

- How to find help with fertility issues

- For partners

- Learn more

What is fertility?

Fertility is the ability to have a child. If you are a woman (or if you have female reproductive organs*), being fertile means you can become pregnant through sexual intercourse. It also means you can carry the baby through pregnancy.

For this to happen, a lot of other things have to take place first.

Your fertility depends on your reproductive organs working as they should. It also depends on certain hormones. Other factors also play a role, including when and how often you have sex and whether your partner has any problems with fertility.

*Learn more about the gender terms used here and how to start the conversation with your cancer care team about your gender identity and sexual orientation in Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Fertility.

What is infertility?

If something in your body changes (like how an organ works or the way certain hormones function) it can be difficult or impossible to conceive a baby naturally or carry the baby to full term.

When you can’t have a child through sexual intercourse with a man who is fertile, this is called infertility, or being infertile.

Doctors usually consider a woman infertile if she can’t conceive a child after 12 or more months of regular sexual activity (or after 6 months if she is more than 35 years old).

Talking to your cancer care team about fertility

Certain cancers, and some cancer treatments, can cause infertility.

If you want to have children after cancer treatment, now is the time to talk to your doctor or cancer care team. Ask them how treatment might affect your fertility and if there is anything you can do to preserve it.

It is best to have these discussions before starting treatment. You might need to be the one to start the conversation. Don't assume your health care team will ask you about your fertility concerns.

Be sure you get the information, support, and resources you need so you can make the best decisions for yourself and your partner. You can learn more about your options in Preserving Your Fertility When You Have Cancer (Women).

If you are part of the LGBTQ+ community

If you are part of the LGBTQ+ community, talk to your cancer care team about your fertility needs, including anything that isn’t addressed here. Studies show that many doctors and nurses don't know the right questions to ask.

Let your cancer care team know your sexual orientation and gender identity, including what sex you were at birth and how you describe yourself now. Also tell them what organs you were born with and about any hormones or gender-affirming procedures you’ve received. Giving them this information will help you get the personalized care you need.

Children and teenagers

Children and teenagers who have cancer are often of special concern because their bodies are still developing. Cancer treatment can affect their reproductive systems and their ability to have children in the future. Learn more in Fertility Preservation in Children and Teens With Cancer.

What causes fertility problems in women with cancer?

You are born with all the eggs you will ever have. These eggs are stored in your ovaries. As you move through puberty, your ovaries release mature eggs every month during your menstrual cycle (called ovulation). The hormones in your body allow this to happen. This continues until you reach menopause and your hormonal cycles eventually stop.

Damage or changes to any part of this process can cause infertility.

Any change in how your ovaries work can affect your fertility. The same is true if there is a change in the hormones your body needs to release an egg from your ovaries each month. These changes can prevent you from getting pregnant (conception), or they can prevent you from carrying a pregnancy to full term.

Cancer and cancer treatment can affect your fertility. This can happen because of:

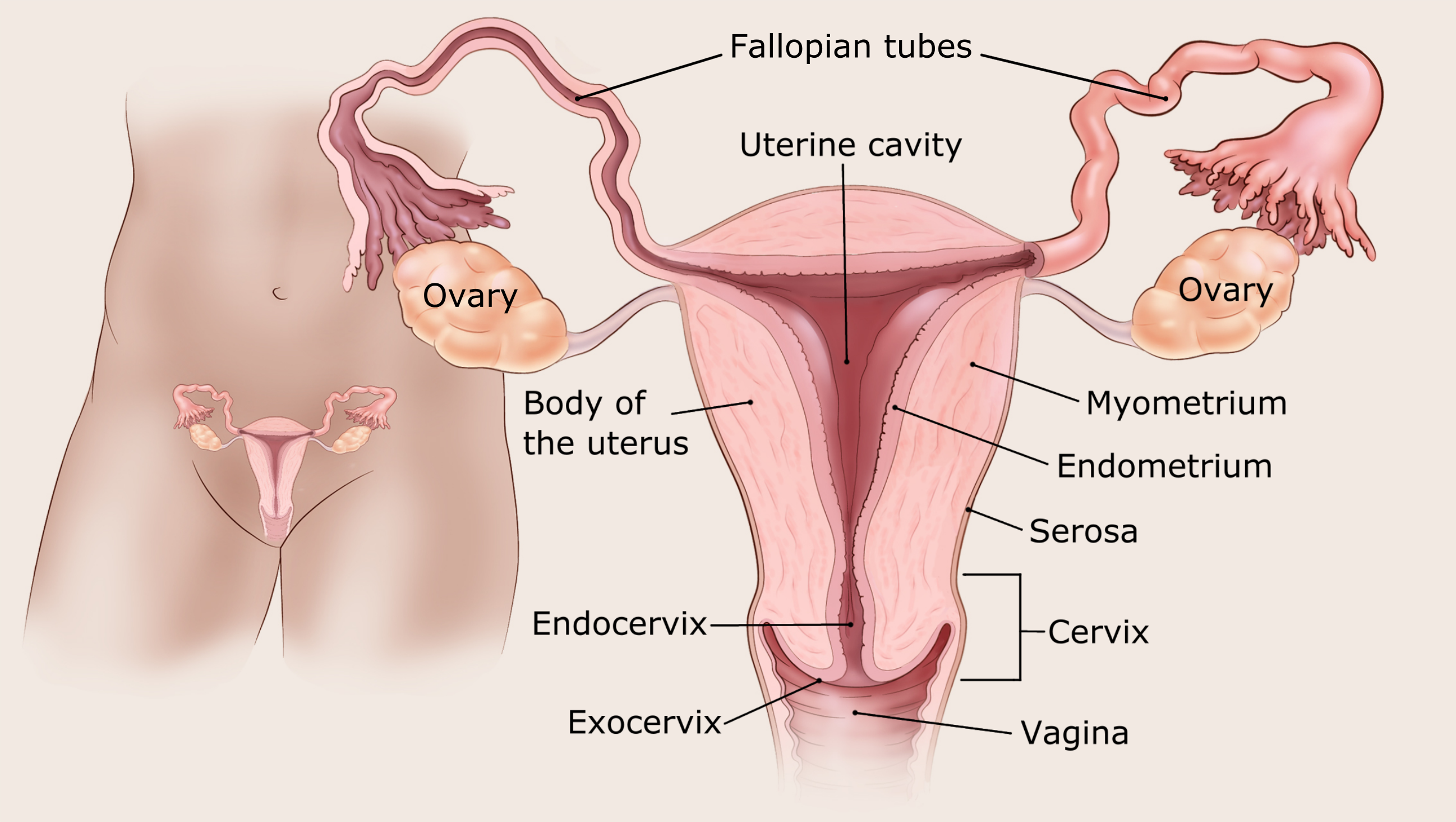

- Damage to organs involved in reproduction (ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix)

- Damage to organs involved in hormone production (ovaries, pituitary gland)

Damage to the ovaries can lower the number of healthy eggs in your body. Because you are born with all the eggs you’ll ever have, losing your healthy eggs can cause infertility. Once your eggs are lost, they can’t be replaced.

Who is more (or less) likely to have fertility problems?

There are certain things that make it more, or less, likely for you to have fertility problems because of cancer and cancer treatment.

Age makes a difference.

The younger you are, the more eggs you usually have in your ovaries. This gives you a higher chance of keeping some fertility in spite of damage from treatments. Women who are treated for cancer before they are 35 have the best chance of becoming pregnant after treatment.

Depending on the treatment they get, some women in their teens or twenties never stop having periods until they reach menopause. Some young women stop having menstrual periods during treatment and then start them again after they are off treatment for a while.

Puberty and menopause make a difference.

After you have chemo, your fertility might not last as long as it otherwise would (if you didn’t need treatment).

You might be at risk of early (premature) menopause if:

- You had chemo before puberty (before your periods began)

- You are a young woman whose menstrual periods return after chemo

When you stop having periods before age 40, this is considered premature ovarian failure or primary ovarian insufficiency. Your ovaries have stopped making the hormones your body needs to be fertile. Of course, if you had surgery to remove your reproductive organs, you also can’t get pregnant.

Having periods doesn’t always mean you are fertile.

Even if your periods return after you stop cancer treatment, you aren’t necessarily fertile. You might need to meet with a fertility expert. They can help you figure out if you are still fertile, and if so, how long your fertility window might last.

Avoiding pregnancy during cancer treatment

Before you start cancer treatment, talk to your doctor or cancer care team about whether you should be on birth control during and after treatment.

Many cancer treatments can harm a developing fetus or cause a miscarriage. It is very important that you don’t get pregnant during treatment.

How cancer treatment affects fertility

For most women, cancer treatment is more likely to interfere with fertility than cancer itself. Each type of treatment might affect your reproductive organs and processes in different ways.

There are other factors that might also affect your fertility, including:

- Your age and stage of development at the time of treatment (before or after puberty, before or after menopause, etc.)

- The type and extent of your surgery

- The type of treatment

- The dose and extent of that treatment

Talk to your doctor and cancer care team about your risk for infertility. If possible, do this before you start cancer treatment. There are steps that can be taken to try and preserve your fertility. It’s best if these are started before treatment begins.

Surgery

Some surgeries to your pelvis or abdomen (belly) might affect your chances of having a baby. This includes surgery for a tumor in your reproductive organs (ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, or cervix) or surgery to your bladder, colon, rectum, or anus.

Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy is surgery done to remove your uterus and cervix. Without a uterus you can’t conceive and carry a child. A hysterectomy might be done for uterine (endometrial) cancer, cervical cancer, or other cancers that affect the reproductive organs.

You might hear people refer to a "simple" or "radical" hysterectomy. A simple hysterectomy usually means removing only the uterus and the cervix. A radical hysterectomy means removing the uterus, cervix, upper part of the vagina, and tissues around the uterus. The ovaries are not always removed during these surgeries.

Some women at high risk for breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, or women who have a hereditary cancer syndrome, might choose to have a hysterectomy and have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed to help prevent the cancers from starting.

Oophorectomy

An oophorectomy is surgery to remove your ovaries. One or both fallopian tubes are often removed at the same time. This surgery is done for ovarian cancer and other cancers that affect the reproductive system. It might be done at the same time as a hysterectomy, or it might be done separately if your uterus isn’t affected.

Since your ovaries hold your eggs, you can’t get pregnant through sexual intercourse without them. If possible, and if there is a low risk that the cancer will come back, the surgeon might try to save one ovary to preserve eggs. In this case, you might be able to get pregnant at a later time. Keeping at least one ovary also preserves the hormones that help prevent menopause symptoms, like hot flashes and vaginal dryness.

Some women at high risk for breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers choose to have an oophorectomy as a way to help prevent the cancers from starting.

Trachelectomy

Trachelectomy is surgery to remove your cervix (the lower part of your uterus) and the upper part of your vagina. The uterus is kept so you have the chance to carry a pregnancy later.

Adhesions

Other types of cancer surgery for tumors in your abdomen or pelvis can sometimes cause scarring (adhesions) around your reproductive organs. This scarring might block your ovaries, fallopian tubes, or uterus, preventing your eggs from being fertilized and implanting in your uterus. This could prevent a pregnancy or not allow it to go full term.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy can affect your fertility if the radiation is aimed at or around your reproductive organs or certain parts of your brain.

Radiation to the abdomen (belly) and pelvis

Radiation to your abdomen (belly) and pelvis can affect your uterus and ovaries. How much of an affect it has will depend on the method of radiation used, the total dose given, and your age and stage of development.

Ovaries: Radiation aimed at or near your ovaries might damage them enough to affect their function. Both external and internal radiation therapy can expose your ovaries to radiation.

Whether or not you become infertile depends on the amount of radiation absorbed by your ovaries. High doses might destroy some or all of the eggs in your ovaries and cause infertility and early menopause. This is more likely to happen if you are older, because the number of eggs in your ovaries decreases over time.

Some eggs might survive if your ovaries can be moved away from the radiation target area in a minor surgery. This could help preserve some eggs and give you a greater chance at keeping your fertility. Or, it could increase the chance that your fertility returns after you finish treatment.

Uterus: Radiation to the uterus can sometimes damage the muscles and blood supply. These problems can limit the growth and expansion of your uterus during pregnancy. Women who had radiation to the uterus have an increased risk of miscarriage, low-birth weight infants, and premature births.

These problems are most likely to happen in women who had radiation during childhood, before the uterus began to grow during puberty. But older women might also be impacted.

Radiation to the brain

Radiation to the brain can sometimes affect your pituitary gland. Your pituitary gland makes hormones that signal your ovaries to start the ovulation process (release of eggs). This may or may not affect your fertility. It depends on the focus and dose of the radiation.

Radiation and pregnancy

Radiation can harm a developing fetus. If there is a chance you’ll remain fertile after radiation, it's important to ask your health care team how long you should wait before having unprotected sex or trying for a pregnancy. They will be able to consider your circumstances and give you specific information.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (chemo) works by killing cells in your body that divide quickly. This includes cancer cells, but also the cells of your ovaries (oocytes).

The oocytes make hormones like estrogen. Your body needs these hormones to release eggs from your ovaries each month and prepare your uterus for pregnancy. Loss of these hormones can affect your fertility. You might go into premature or early menopause. This can be temporary or permanent.

Some chemo medicines can also lower the number of eggs in your ovaries, making it harder to get pregnant after treatment.

Whether or not you are fertile after chemo depends on your age and stage in life, such as if you’ve gone through puberty or are nearing menopause. Other factors include your hormone levels after chemo, the type of cancer you have, and the type and dose of chemo you get.

Chemo medicines that are most likely to cause infertility in women are:

- Busulfan

- Carmustine

- Chlorambucil

- Cyclophosphamide

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- Lomustine

- Mechlorethamine (Mustargen)

- Melphalan

- Procarbazine

Other chemo medicines can also affect fertility.

Higher doses of chemo are more likely to cause fertility changes that don’t get better. The same is true if you get more than one of these medicines. Ongoing infertility is also more likely when you are treated with both chemo and radiation therapy to the belly (abdomen) or pelvis.

Talk to your cancer care team about the chemo medicines you will get and your risk of infertility from them.

Chemo and pregnancy

It's very important to not get pregnant during chemo. Many chemo medicines can harm an unborn baby. This can lead to birth defects and miscarriage. If there is a chance you could get pregnant during treatment, it’s important to use effective birth control. Talk to your cancer care team about your best options.

Some women can get pregnant even when their periods have stopped, so it’s important to use birth control whether or not you have periods. Talk to your cancer care team about what's best for you.

If you want to get pregnant after treatment ends, be sure you know how long you should wait before trying. You can learn more about this in Having a Baby After Cancer (Pregnancy).

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy works by lowering the level of certain hormones or by keeping them from working the way they should.

Since your body needs these hormones to conceive and carry a pregnancy, not having enough of them might make it hard to become pregnant or to carry a baby to full term. Some of these medicines might also cause birth defects.

Some hormone therapies can put you into an early menopause. This may be temporary or permanent, depending on your age and the type and length of your treatment.

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy

There haven’t been enough studies done to fully understand which targeted therapies and immunotherapies can cause infertility or pregnancy problems. But here is what’s known so far:

Many targeted therapy medicines interfere with functions your body needs for healthy ovaries and fertility. Because of this, these medicines might increase your chances of infertility after treatment. For example, bevacizumab (Avastin) has been linked to ovarian failure, which can be permanent.

Some immunotherapy medicines have also been shown to interfere with fertility, and with having a healthy pregnancy after treatment. For example, the targeted medicines thalidomide and lenalidomide carry a high danger of causing birth defects. Women who are given these medicines are asked to use two effective types of birth control while taking them.

In addition, studies show that some immune checkpoint inhibitors (another type of immunotherapy medicine) might increase the risk of pregnancy complications such as birth defects.

More studies are taking place. In the meantime, talk with your doctor or cancer care team about your risk of infertility and what can be done to help preserve it.

Bone marrow or stem cell transplant

Having a bone marrow or stem cell transplant often means you will get high doses of chemo and sometimes radiation to your whole body to prepare for the transplant. This treatment might permanently stop your ovaries from working normally, causing infertility. Talk with your doctor or cancer care team about this risk before starting treatment.

Evaluating menstruation and fertility after cancer treatment

If you have regular menstrual periods after cancer treatment, your chances of being fertile are higher. But having your period doesn’t always mean you’ll be able to have a baby.

For some women, cancer treatment stops menstrual periods permanently. This is called early menopause. It causes permanent infertility.

For other women, menstrual periods stop during treatment but return later. Women who have periods after cancer treatment may still be less fertile. Even if you menstruate during treatment and remain fertile afterward, you might still have trouble conceiving a child.

Older women and women who had higher doses of radiation therapy or chemo are less likely to restart their periods after treatment. If their period does start again, it may take longer to come back.

Children and younger women have a larger ovarian reserve (more ovaries left in their bodies). They are less likely to go through menopause or become infertile. But some younger women might still lose their fertility. Radiation therapy to the pelvis and abdomen (belly) and higher doses of chemo may cause even young girls to go through menopause.

Your doctor can refer you for ovarian reserve testing. This is done by using sensitive hormonal tests, such as the anti-Müllerian hormone. Results of these tests might help your doctor determine how likely you are to get pregnant or if you will need fertility assistance.

How to find help with fertility issues

If you have trouble getting pregnant after cancer treatment, think about meeting with a reproductive endocrinologist. This is a doctor who specializes in fertility issues. Some reproductive endocrinologists specialize in cancer-related fertility.

For partners

Partners often share the same concerns about fertility as the person with cancer. If your partner is going through treatment, it’s important for both of you to get the support you need.

Depending on the situation and your desire for having children, you can work together to find possible options for preserving fertility or for having a child once treatment ends. This can help reassure both you and your partner. It can help you both cope with the changes that are happening and challenges that lie ahead.

Going with your partner to treatment, follow-up visits, and check-ups might be a good idea, too. You can also ask for a referral to a counselor, therapist, or fertility specialist.

Learn more

- Written by

- References

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Fertility Concerns and Preservation for Women. Accessed at cancer.net. Content is no longer available.

Cardonick EH. Cancer survivors: Overview of fertility and pregnancy outcomes. In, UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate. Accessed at uptodate.com on July 16, 2024.

Gougis P, Hamy A, Jochum F, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Use During Pregnancy and Outcomes in Pregnant Individuals and Newborns. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e245625.

Griffiths MJ, Winship AL, Hutt KJ. Do cancer therapies damage the uterus and compromise fertility? Hum Reprod Update. 2019. [Epub ahead of print.]

Hadjar J. Altered sexual and reproductive fertility. In: Olsen M, LeFebvre KB, Walker SL, Dunphy EP, eds. Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy: Guidelines and Recommendations for Practice. Oncology Nursing Society; 2023: 643-655.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). Fertility issues in girls and women with cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/fertility-women on July 30, 2024.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Survivorship. Version 1.2024. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf on July 30, 2024.

Oktay et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(19):1994-2003.

Rosario R, Cui W, Anderson RA. Potential ovarian toxicity and infertility risk following targeted anti-cancer therapies. Reprod Fertil. 2022;3(3):R147-R162. Published 2022 Jul 11.

Rozen G, Rogers P, Chander S, et al. Clinical summary guide: reproduction in women with previous abdominopelvic radiotherapy or total body irradiation. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020(4):hoaa045. Published 2020 Oct 25.

Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies. A patient’s guide to assisted reproductive technology. Accessed at https://www.sart.org/patients/a-patients-guide-to-assisted-reproductive-technology/ on July 30, 2024.

Last Revised: January 17, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.