How Cancer And Cancer Treatment Can Affect Fertility in Men

Some cancers and cancer treatments can cause changes in your body that affect your fertility (your ability to have a child). This could include hormone changes or damage to certain parts of your body.

Learn more about how cancer and its treatment can affect fertility in men, and how to find help with fertility issues.

- What is fertility?

- What is infertility?

- Talking to your cancer care team about fertility

- What causes fertility problems in men with cancer?

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Hormone therapy

- Targeted therapy and immunotherapy

- Bone marrow or stem cell transplant

- Evaluating fertility after cancer treatment

- How to find help with fertility issues

- For partners

- Learn more

What is fertility?

Fertility is the ability to have a child. If you are a man (or if you have male reproductive organs*), being fertile means you can father a child through sexual intercourse.

For this to happen, a lot of other things must take place first.

Your fertility depends on your reproductive organs working as they should. It also depends on certain hormones. Other factors also play a role, including when and how often you have sex and whether your partner has any fertility issues.

*Learn more about the gender terms used here and how to start the conversation with your cancer care team about your gender identity and sexual orientation in Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Fertility.

What is infertility?

If something in your body changes (like how an organ works or not making enough of certain hormones) it can be difficult or impossible to father a baby naturally.

When you can’t have a child through sexual intercourse, this is called infertility, or being infertile. Doctors usually consider a man infertile if he can’t father a child after 12 or more months of regular sexual activity.

Talking to your cancer care team about fertility

Certain cancers, and some cancer treatments, can cause infertility.

If you want to have children after cancer treatment, talk to your doctor or cancer care team while you are deciding on treatment. Ask them how treatment might affect your fertility and if there is anything you can do to preserve it.

It’s best to have these discussions before starting treatment. You might need to be the one to start the conversation. Don't assume your health care team will ask you about your fertility concerns.

Be sure you get the information, support, and resources you need so you can make the best decisions for yourself and your partner. You can learn more about your options in Preserving Fertility in Men With Cancer.

If you are part of the LGBTQ+ community

If you are part of the LGBTQ+ community, talk to your cancer care team about your fertility needs, including anything that isn’t addressed here. Studies show that many doctors and nurses don't know the right questions to ask.

Let your cancer care team know your sexual orientation and gender identity, including what sex you were at birth and how you describe yourself now. Also tell them what organs you were born with and about any hormones or gender-affirming procedures you’ve received. Giving them this information will help you get the personalized care you need.

Children and teenagers

Children and teenagers who have cancer are often of special concern because their bodies are still developing. Cancer treatment can affect their reproductive systems and their ability to have children in the future. Learn more in Fertility Preservation in Children and Teens With Cancer.

What causes fertility problems in men with cancer?

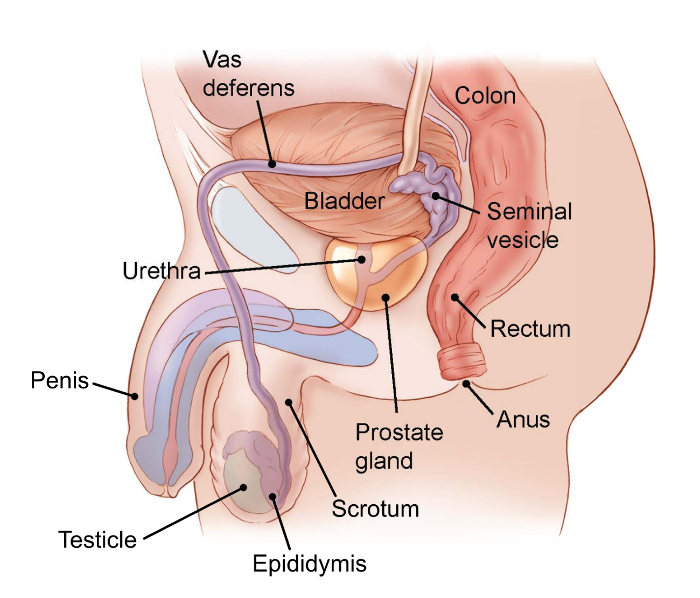

To father a child through sexual intercourse, your body must be able to make enough healthy sperm. The sperm must then travel from your testicles to your urethra. Once the sperm is there, you have to be able to get an erection and ejaculate (discharge) the sperm from your penis. Your body also has to make the hormones that control all of this.

Damage or changes to any part of this process can cause infertility. This includes:

- Hormone changes

- Damage to any part of your body involved in reproduction

- Damage to the nerves that make these body parts function

- Blockages or damage to the route that moves sperm from your testicles to your urethra

These things can happen because:

- A tumor blocks or presses on a reproductive organ, so the organ doesn’t work properly.

- Your body doesn’t make enough of the hormones needed for sperm production or sexual activity.

- Your testicles don’t make healthy sperm.

- Your testicles make less sperm, or no sperm at all.

You might also be at higher risk of infertility because of:

- Age: As a man gets older, it’s common for his testicles to make fewer sperm and for the sperm quality to decrease. Older men are more likely to become infertile after cancer treatment.

- Puberty: The testicles start making sperm during puberty. Boys who have gone through puberty by the time of cancer treatment are more likely to have fertility issues compared to boys who haven’t gone through puberty.

Surgery

Some surgeries to your pelvis or abdomen (belly) can damage your reproductive organs or the nerves that make them work. This includes surgery for a tumor in your reproductive organs (testicles, prostate, or penis) or surgery to your bladder, colon, or rectum. Surgery for any of these cancers might affect your fertility.

Testicular cancer surgery

If you have testicular cancer, you will most likely need at least one of your testicles removed. This is called an orchiectomy.

Often, only one testicle needs to be removed. If your other testicle is healthy, you can probably still make sperm and father a child after surgery. But some men with testicular cancer have poor fertility because the testicle that is left doesn’t work well.

For this reason, sperm banking before a testicle is removed is now recommended for men and boys who want to preserve their fertility. This is called fertility preservation. You can learn more about this in Fertility Preservation in Men and Hormone Concerns in Boys and Men with Testicular Cancer.

Prostate cancer surgery

Men who have certain kinds of surgery for prostate cancer may develop fertility issues.

Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy removes the prostate gland and seminal vesicles, which make semen. It is an option if the cancer hasn’t spread beyond the prostate gland.

If you have this surgery, your body will no longer be able to make semen or release sperm during sex. You can still have an orgasm, but no fluid will come out of your penis.

Surgery to remove your prostate can also damage the nerves that allow you to get an erection, causing erectile dysfunction (ED). If this happens, you might not be able to get enough of an erection for sexual intercourse.

If you can get an erection and have orgasms, you still won’t be able to father a child through sex because no semen will come out. When your prostate gland is removed, your testicles still make sperm, but the tubes (vas deferens) that deliver sperm to your urethra are cut and tied off. This prevents the flow of sperm out of your testicles.

Even after this surgery, there still are ways to get sperm from your testicles. This sperm can be used to fertilize a woman’s eggs and father a child.

Bilateral orchiectomy

Bilateral orchiectomy removes both testicles. Removing both testicles stops your body from making testosterone. This acts as a type of hormone therapy which can slow the growth of prostate cancer cells. This surgery is most often done when the cancer has spread outside the prostate and surgery can’t get rid of all the cancer.

If you have this surgery, you won’t be able to make sperm cells, so you won’t be able to father children. Sperm banking before surgery may be an option if you want to father children in the future.

Bladder cancer surgery (radical cystectomy)

For this surgery your bladder, prostate, and seminal vesicles are all removed. Without your prostate gland and seminal vesicles, you can’t make semen or release sperm during sex. You can still have an orgasm (climax), but no fluid will come out of your penis.

Surgery to remove your bladder can also damage the nerves that allow you to get an erection, causing erectile dysfunction (ED). If this happens, you might not be able to get enough of an erection for sexual intercourse.

If you can get an erection and have an orgasm, you still won’t be able to father a child through sex because no semen will come out. When your prostate is removed, your testicles still make sperm, but the tubes (vas deferens) that deliver sperm to your urethra are cut and tied off. This prevents the flow of sperm out of your testicles.

Even after this surgery, there are still ways to get sperm from your testicles which can be used to fertilize a woman’s eggs and father a child.

Surgery to remove lymph nodes

Surgery for testicular cancer and some colorectal cancer surgeries may including removing lymph nodes (part of your body’s immune system) from your lower belly (abdomen) or pelvis. Surgery to remove these lymph nodes can damage nerves that are needed to ejaculate during sex.

When these nerves are affected, your body still makes semen, but it doesn’t come out of your penis during orgasm. Instead, it either flows backward into your bladder (called retrograde ejaculation) or it stays in your urethra. Medicines can sometimes make it possible for you to ejaculate semen out of your penis again.

Radiation therapy

Radiation aimed at the testicles, or nearby pelvic areas, can kill the stem cells that make sperm. This can affect your fertility.

Testicular cancer

Radiation is sometimes used in the treatment of early-stage seminoma (a type of testicular cancer). It is used to treat nearby lymph nodes where the cancer might have spread.

During this treatment, the remaining testicle is usually shielded to protect it from direct radiation exposure. However, radiation can scatter once it enters the body, so it may still impact the testicles. This can lead to fertility problems, either temporary or permanent.

Some men stay fertile while getting radiation treatments, but their sperm might be damaged. Damaged sperm can cause pregnancy problems and birth defects. It’s important to wait at least 6 months (and sometimes up to 2 years) before having unprotected sex or trying for a pregnancy.

Your doctor will be able to consider your situation and give you specific information about how long you should wait.

Prostate cancer

There are two types of radiation that might be used to treat prostate cancer.

Internal radiation (brachytherapy)

Internal radiation (brachytherapy) is given by placing radioactive seeds into the prostate. These seeds give off a lower dose of radiation over a longer period of time. With this method, the testicles are exposed to a much lower dose of radiation with less damage done to sperm cells.

Many men remain fertile or start making sperm again after treatment is done. However, the radioactive seeds stay in place for a period of time. So be sure you understand any restrictions you need to follow during and after brachytherapy.

Ask your cancer care team if you should:

- Avoid sexual intercourse, and for how long

- Use birth control, and for how long

- Limit close contact with pregnant woman and children, and for how long

External beam radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy is also used for some people with prostate cancer. Beams of radiation are focused on the prostate gland from a machine outside the body. It can be used to try to cure earlier-stage cancers, to treat cancers that have grown outside the prostate, or to help relieve symptoms.

This type of radiation treatment is more likely to cause permanent infertility, even if your testicles are shielded.

Childhood leukemia

Radiation therapy is sometimes used to treat certain childhood leukemias. Radiation to the testicles may be done if tests show the leukemia has spread there. Children who receive radiation to the testicles are likely to become infertile, so fertility preservation options should be discussed.

Learn more: Preserving Fertility in Children and Teens with Cancer

Some children with leukemia may also need radiation to the brain. This can affect the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. These glands work together to release hormones needed to make testosterone and produce sperm. Not having enough of these hormones can lead to infertility.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (chemo) works by killing cells in your body that divide quickly. This includes cancer cells, but also the cells that make sperm. With some chemo, your sperm production might slow down or stop.

Temporary infertility happens when sperm production returns after treatment ends. This can take time, even years. And your sperm production may never return to pretreatment levels. This may or may not affect your fertility.

Permanent infertility can happen if the cells in your testicles that divide to make new sperm (spermatogonial stem cells) are damaged to the point that they can no longer produce maturing sperm cells.

Chemo medicines that are most likely to cause infertility in men are:

- Busulfan

- Carmustine

- Chlorambucil

- Cisplatin

- Cyclophosphamide

- Ifosfamide

- Lomustine

- Melphalan

- Procarbazine

Other chemo medicines can also affect fertility, but less often.

Higher doses of these chemo medicines are more likely to cause permanent fertility changes. Getting more than one of these medicines can have greater effects. The risks of permanent infertility are even higher when men are treated with both chemo and radiation therapy to the abdomen (belly) or pelvis.

Talk to your doctor about the chemo medicines you will get and the fertility risks that come with them.

Avoiding partner pregnancy during and after chemo

It’s important to not get your partner pregnant while you’re getting chemo. Even if you remain fertile, your sperm may be damaged during treatment. This can lead to birth defects and other pregnancy complications for your partner.

After treatment, many doctors suggest waiting 6 months before trying to father a child. This is to allow damaged sperm enough time to repair or to be cleared from the body. Ask your doctor about the best timeframe for you.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapies used to treat prostate cancer or other cancers can decrease levels of the male hormones needed to make sperm and get an erection. This can affect your ability to have a child.

These medicines can also cause sexual side effects, like a lower sex drive and problems with erections. The decrease in sperm production and the sexual side effects tend to improve once these medicines are stopped.

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy

Some targeted therapy and immunotherapy medicines might affect your fertility. Research is still being done to find out which of these medicines affect male fertility. Ask your cancer care team if the medicines you will be getting are likely to cause fertility problems.

Thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide (immunomodulatory drugs – ImiDs) are known to cause birth defects in an unborn child (fetus). A woman can be exposed to these medicines during sexual intercourse with a man who is currently taking them or has taken them in the last 4 weeks.

If you are taking an IMiD and your sexual partner is able to get pregnant, it’s essential that you use very effective forms of birth control.

This might include a condom for you and a long-acting hormone contraceptive or IUD for your partner. These precautions should start as soon as you begin the medicine and continue for at least 4 weeks after you finish taking it.

Bone marrow or stem cell transplant

Having a bone marrow or stem cell transplant often means you will get high doses of chemo and sometimes radiation to prepare for the transplant.

This treatment might permanently prevent you from making sperm, causing infertility. Talk with your doctor or cancer care team about this risk before starting treatment.

Evaluating fertility after cancer treatment

Some men remain fertile during cancer treatment, but others do not. For some men, infertility is temporary and they will regain their ability to make healthy sperm over time.

Sperm analysis is the main way fertility is measured. As you get further from treatment, these tests can be repeated to look for recovery of your sperm production. Blood tests of your hormone levels may also be done to get more information about what is causing your infertility.

How to find help with fertility issues

If you have trouble getting your partner pregnant after cancer treatment, think about meeting with a reproductive endocrinologist. This is a doctor who treats fertility issues. Some reproductive endocrinologists specialize in cancer-related fertility.

For partners

Partners often share the same concerns about fertility as the person with cancer. If your partner is going through treatment, it’s important for both of you to get the support you need.

Depending on the situation and your desire for having children, you can work together to find possible options for preserving fertility or for having a child once treatment ends. This can help reassure both you and your partner. It can also help you both cope with the changes that are happening and the challenges that lie ahead.

Going with your partner to treatment, follow-up visits, and check-ups might be a good idea, too. You can also ask for a referral to a counselor, therapist, or fertility specialist.

Learn more

- Written by

- References

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Fertility Concerns and Preservation for Men. Accessed at cancer.net. Content is no longer available.

Cardonick EH. Cancer survivors: Overview of fertility and pregnancy outcomes. In, UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate. Accessed at uptodate.com on August 14, 2024.

Drugs.com. Revlimid. Drugs.com. Accessed at https://www.drugs.com/revlimid.html on August 14, 2024.

Hadjar J. Altered sexual and reproductive fertility. In: Olsen M, LeFebvre KB, Walker SL, Dunphy EP, eds. Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy: Guidelines and Recommendations for Practice. Oncology Nursing Society; 2023: 643-655.

Hayes FJ, Bubley GJ. Effects of cytotoxic agents on gonadal function in adult men. In, UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate. Accessed at uptodate.com on August 6, 2024.

Marino M, Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, Crafa A, La Vignera S, Calogero AE. New Insights of Target Therapy: Effects of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors on Male Gonadal Function: A Systematic Review. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2024 May 29;22(5):102131.

Martins da Silva S, Anderson RA. Reproductive axis ageing and fertility in men. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022;23(6):1109-1121.

Mourmouris P, Tzelves L, Deverakis T, et al. Prostate Cancer Therapies and Fertility: What Do We Really know?. Hellenic Urology. 2020; 32(4): 53-156.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). Fertility issues in boys and men with cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/fertility-men on August 5, 2024.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Survivorship.Version 1.2024. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf on August 5, 2024.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Testicular cancer. Version 1.2024. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/testicular.pdf on August 13, 2024.

Ntemou E, Delgouffe E, Goossens E. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Male Fertility: Should Fertility Preservation Options Be Considered Before Treatment? Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(6):1176.

Oktay et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(19):1994-2003.

Parekh NV, Lundy SD, Vij SC. Fertility considerations in men with testicular cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2020; 9(Suppl 1): S14-S23.

Last Revised: January 17, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.