Cancer, Sex, and the Female Body

When a person is diagnosed with cancer, they may wonder how ‘normal’ life can and will be if they need to go through surgery or treatment, or as they adjust to living as a survivor. Many times a person with cancer wonders how the diagnosis and treatment might affect their sex life.

Sex, sexuality, and intimacy are just as important for people with cancer as they are for people who don’t have cancer. In fact, sexuality and intimacy have been shown to help people face cancer by helping them deal with feelings of distress, and when going through treatment. But, the reality is that a person's sex organs, sexual desire (sex drive or libido), sexual function, well-being, and body image can be affected by having cancer and cancer treatment. How a person shows sexuality can also be affected. Read more in How Cancer and Cancer Treatment Can Affect Sexuality.

The information here is for adult females who want to learn more about how cancer and cancer treatment can affect their sex life. We cannot answer every question, but we’ll try to give you enough information for you and your partner to have open, honest talks about intimacy and sex. We’ll also share some ideas to help you talk with your doctor and your cancer care team.

If you are lesbian, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) or gender non-conforming, you may have needs that are not addressed here. It's very important to talk to your cancer care team and give them information about your sexual orientation and gender identity, including what sex you were at birth, how you describe yourself now, any procedures you’ve had done, or hormone treatments you may have taken or are taking.

The 1st step: good communication

It’s important to know that you can get answers to these questions and help if you are having sexual problems. The first step is to bring up the topic of sex with your doctor or someone on your partner and cancer care team. It’s very important to talk with your cancer care team about what to expect, and continue to talk about what's changing or has changed in your sexual life as you go through procedures, treatments, and follow-up care. This includes letting them know what over-the-counter and prescription medications, vitamins, or supplements you may be taking because they might interfere with treatments.

Don't assume your doctor or nurse will ask you about these and other any concerns you have about sexuality. Many studies have found that doctors, nurses, and other members of a health care team don’t always ask about sexuality, sexual orientation, or gender identity during check-ups and treatment visits. Because of this, patients might not get enough information, support, or resources to help them deal with their feelings and sexual problems.

Questions to ask

You probably have certain questions and things you're wondering about. Here are some questions you may want to ask your doctor or nurse to jump start talks about having sex during and after treatment:

- How might treatment affect my sex life?

- Is it safe to have sex now? If not, when will it be OK to have sex?

- Are there any types of sex I should avoid?

- Do I need birth control or other protection during treatment? How about afterwards? For how long?

- Can my medications or treatment be passed to my partner through my body fluids?

- What safety measures do I need to take, and for how long?

The 2nd step: Understanding how your body works

Understanding the female sex organs

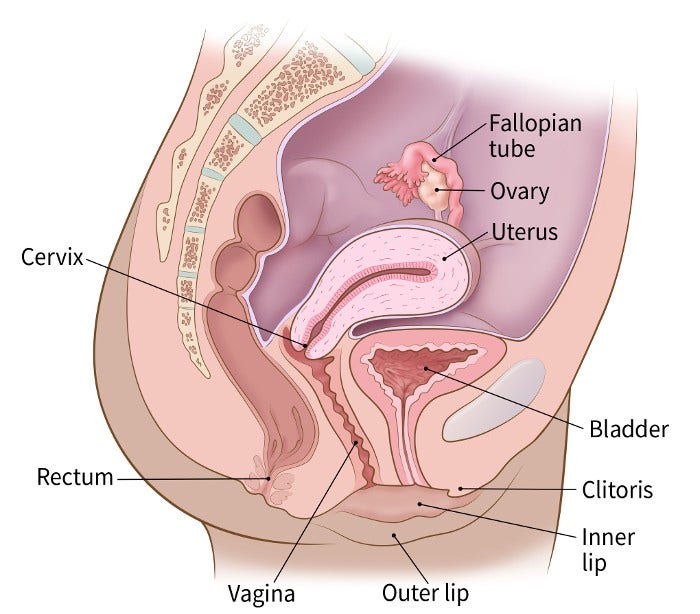

A woman’s genitals and organs for pregnancy are in the pelvis (the lower part of the belly). These are some organs that are in the pelvis, including sex organs and other nearby organs. Cancer of any of these organs or cancer treatment in this area can affect your sex life:

- Uterus – the pear-shaped organ that holds a growing baby

- Fallopian tubes – 2 thin tubes that carry eggs from the ovaries to the uterus

- Ovaries – 2 small organs that store eggs and make hormones

- Cervix – the lower part of the uterus at the top of the vagina

- Vagina – a 3- to 4-inch tube that connects the cervix to the outside of the body

- Vulva – the outside parts, such as the clitoris and the inner and outer lips

- Bladder – the hollow, balloon-like organ that holds urine

- Rectum – the bottom end of the intestines that connects to the outside of the body

Side view of woman’s pelvis

Female genitals

Many women have never looked at their genitals, and may not know for sure which parts are where.

If you feel comfortable doing so, take a few minutes with a hand mirror to examine yourself.

- The outside part is called the vulva.

- Find the outer lips (labia majora) and inner lips (labia minora). They act like pillows to protect the sensitive parts in the middle. Many women find that gentle touch on the inner lips feels good.

- Next find the clitoris, a small bump covered by a little hood of skin. It’s right in the middle, above the opening of the vagina. The clitoris is the part of a woman’s body most sensitive to pleasure with caressing.

- Just under the clitoris is a little slit where urine comes out. This is the opening of a short tube (the urethra) which drains the bladder (storage bag for urine).

- Below the opening of the vagina is the anus, where stool come out. The anus is the very end of the system that digests food. Some women enjoy being touched around and even inside the anus. If you or a partner puts a finger or a sex toy in the anus, do not use it to caress the vagina, since that could cause an infection with bacteria that are healthy in the anus, but not in the vagina.

You may also want to try touching each area lightly to find out where you are most sensitive.

Has your cancer treatment changed the look of your outer genitals in any way? If so, take time to get used to the changes. Check to see if any areas are sore or tender. Share what you learn about yourself with your partner. Work together to have sex that pleases you both.

The natural cycles of the mature female body

In order to talk about sex, it helps to know about the structures and hormones that are also involved with having children and how they work together.

During the years when a woman can have children, her ovaries take turns each month producing a ripe egg. When the egg is released, it travels through the fallopian tube into the uterus. A woman can get pregnant (naturally) if a sperm cell travels through the cervix and joins the egg. The cervix is the gateway for sperm to get into the body and for a baby passing out of the body at birth.

If a woman does not become pregnant, the lining of the uterus that has built up over the past weeks flows out of her cervix as the “blood” of her period. If she gets pregnant, the lining stays in place to feed the growing baby.

The regular cycles the mature female body goes through each month are controlled by hormones.

Hormones

The main hormones that may help a woman feel desire are called estrogens and androgens. Androgens are thought of as “male” hormones, but women’s bodies also make small amounts of them. About half of the androgens in women are made in the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys. The ovaries make the rest of a woman’s androgens. Estrogen comes mostly from the ovaries.

The ovaries usually stop sending out eggs and greatly reduce their hormone output around age 50, though the age varies. This is called menopause or “the change of life.” Some women fear that their sexual desire will go away with menopause. But for many women, the drop in ovarian hormones doesn’t change their desire for sex. Still, it can take longer for the vagina to enlarge and get moist. Low estrogen levels can also cause the lining of the vagina to get thinner and lose some of its ability to stretch. In some women, the vagina may stay tight and dry, even if they are very aroused.

Female orgasm

As a woman becomes sexually excited, her nervous system sends signals of pleasure to her brain. The signals may trigger the orgasm reflex. During orgasm, the muscles around the genitals contract in rhythm. The muscle tension and release sends waves of pleasure through the genital area and sometimes over the entire body. An orgasm is a natural reflex, but most women need some experience in learning to trigger it.

A woman’s orgasms may change over time. As she gets older, orgasms may take longer to reach, and more mental excitement and touching may be needed.

There are many sources of excitement that lead to orgasm. They differ for each woman. A few women can reach orgasm just by having a vivid fantasy about sex or by having their breasts stroked. Others have had an orgasm during a dream while asleep. But most women need some caressing of their genitals to reach orgasm.

The areas of a woman’s genitals that are most sensitive to touch are the clitoris and the inner lips. When a woman becomes sexually excited, the entire genital area swells. It also turns a darker pink as blood rushes in under the skin.

Many women reach orgasm most easily when the clitoris is stroked. Like a penis, the clitoris has a head and a shaft. It sends messages of pleasure to the brain when it’s stroked.

The head of the clitoris is so sensitive that it can become sore from direct rubbing that’s either too fast or too hard. Soreness can be prevented by using a lubricant and by stroking or touching close to, but not on, the head of the clitoris.

Other areas, including the outer lips and anus, can also give a woman pleasure when stroked. Each woman’s sensitive zones are a little different. The opening of the vagina contains many nerve endings. It’s more sensitive to light touch than the deep end of the vagina. For some women, the front wall of the vagina is more sensitive to pressure during sex than the back wall. Some sex therapists suggest that stroking an area about 1 to 4 inches deep on the front wall of the vagina helps some women reach orgasm during sex.

The 3rd step: Keep talking and work together to manage problems

Learn as much as you can about the possible effects your cancer treatment may have on your sex life. Talk with your doctor, nurse, or any other member of your cancer care team. When you know what to expect, you can plan how you might handle those issues.

Keep in mind that, no matter what kind of cancer treatment you get, most women can still feel pleasure from touching. Few cancer treatments (other than those affecting some areas of the brain or spinal cord) damage the nerves and muscles involved in feeling pleasure from touch and reaching orgasm. For example, a woman whose vagina is painfully tight or dry can often reach orgasm through stroking of her breasts and outer genitals.

Try to keep an open mind about ways to feel sexual pleasure. Some couples have a narrow view of what normal sex is. If both partners cannot reach orgasm through or during penetration, some may feel disappointed. But during and after cancer treatment, there may be times when the kind of sex you like best is not possible. Those times can be a chance to learn new ways to give and receive sexual pleasure. You and your partner can help each other reach orgasm through touching and stroking. At times, just cuddling can be pleasurable. You could also continue to enjoy touching yourself. Do not stop sexual pleasure just because your usual routine has been changed.

Try to have clear, 2-way talks about sex with your partner and with your cancer care team. If you’re too embarrassed to ask your team whether sexual activity is OK, you may never find out. Talk to your team about sex, and tell your partner what you learn. Good communication is the key to adjusting your sexual routine when cancer changes your body. If you feel weak or tired and want your partner to take a more active role in touching you, say so. If some part of your body is tender or sore, you can guide your partner’s touches to avoid pain. Keep in mind that if one partner has a sex problem, it affects both of you.

Boost your self-esteem. Remind yourself about your good qualities. If you lose your hair, you may choose to wear a wig, hat, or scarf if it makes you feel more comfortable. You may choose to wear a breast form (prosthesis) if you’ve had a breast removed. Do whatever makes you feel good about yourself. Eating right and exercising can also help keep your body strong and your spirits up. Practice relaxation techniques, and get professional help if you think you are anxious, depressed, or struggling.

- Written by

- References

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Practice bulletin no. 213: Female sexual dysfunction. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;134:e1-18.

Carter et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(5):492-513.

Faubion SS, Rullo JE. Sexual dysfunction in women: A practical approach. American Family Physician. 2015;92(4):281-288.

Katz A. Breaking the Silence on Cancer and Sexuality: A Handbook for Healthcare Providers. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society.; 2018.

Katz, A. Woman Cancer Sex. Pittsburgh: Hygeia Media, 2010.

Moment A. Sexuality, intimacy, and cancer. In Abrahm JL, ed. A Physician’s Guide to Pain and Symptom Management in Cancer Patients. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014:390-426.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Survivorship [Version 2.2019]. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf on January 31, 2020.

Nishimoto PW, Mark DD. Sexuality and reproductive issues. In Brown CG, ed. A Guide to Oncology Symptom Management. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2015:551-597.

Zhou ES, Bober SL. Sexual problems. In DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, eds. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019:2220-2229.

Last Revised: February 6, 2020

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.