If You Have Uterine Sarcoma

What is a uterine sarcoma?

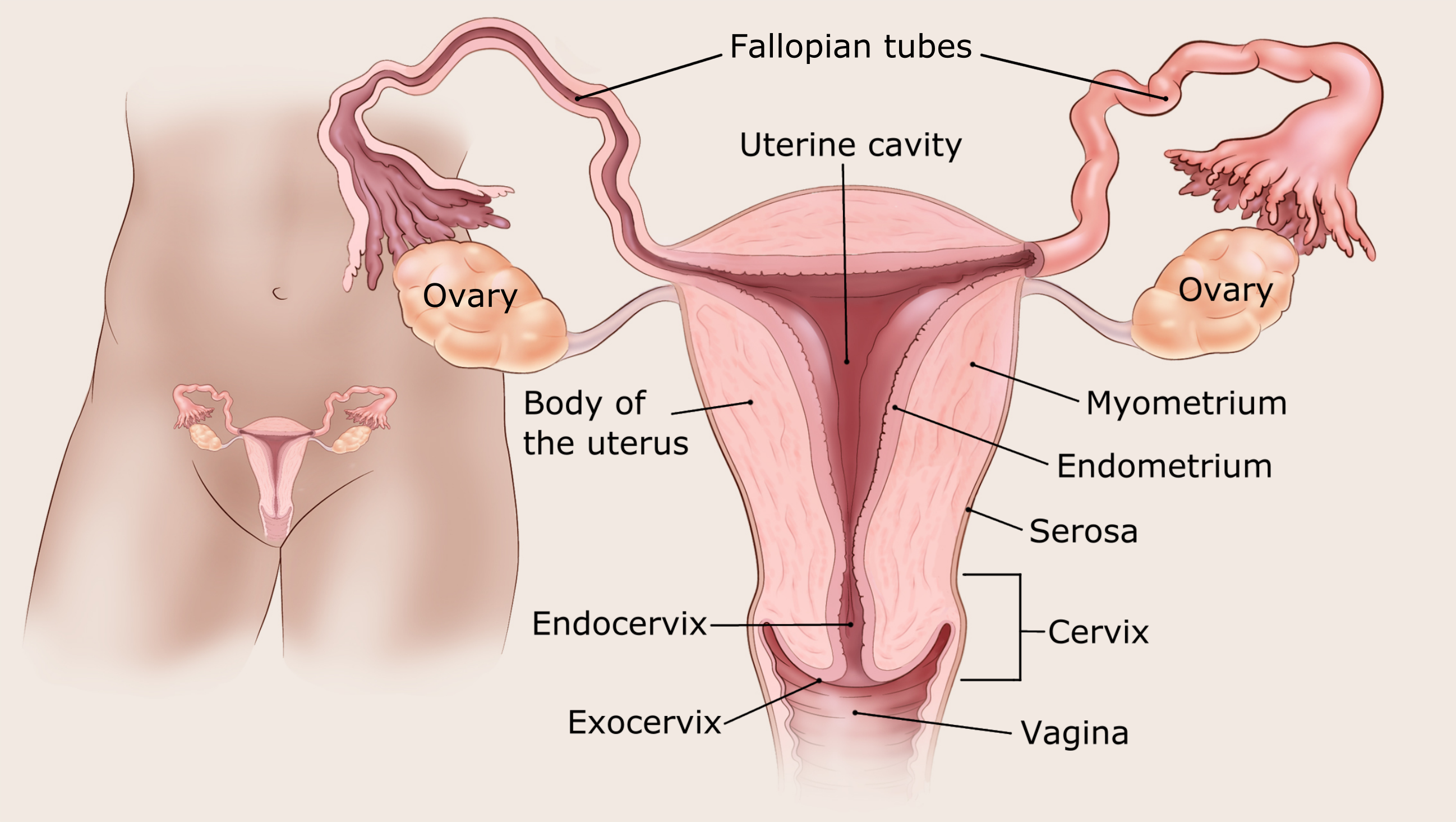

Cancer that starts in the muscle wall or the tissue that supports the uterus is called uterine sarcoma. This cancer starts when the cells grow out of control and crowd out normal cells.

Uterine sarcoma is rare. Many people often mean endometrial cancer when they say uterine cancer. Endometrial cancer is much more common. It starts in the lining of the uterus. It's not the same as uterine sarcoma.

Cancer cells can spread to other parts of the body. When cancer cells do this, it’s called metastasis. Sarcoma cells in the uterus can sometimes travel to lungs or the bone and grow there. The cancer cells in the new place look just like the ones from the uterine sarcoma.

Cancer is always named for the place where it starts. So if uterine sarcoma spreads to the lung (or any other place), it’s still called uterine sarcoma. It’s not called lung cancer unless it starts from cells in the lung.

Ask your doctor to use these pictures to show you where your cancer is.

Different types of uterine sarcoma

There are several types of uterine sarcoma. Each type is based on the kind of cell it starts in. The most common type of uterine sarcoma is called uterine leiomyosarcoma. These cancers start in the cells that make up the part of the uterus muscle wall called the myometrium.

Your doctor can tell you more about the type you have.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Why do you think I have cancer?

- Is there a chance I don’t have cancer?

- Would you please write down the kind of cancer you think I might have?

- What will happen next?

How does the doctor know I have uterine sarcoma?

Uterine sarcoma may not be found until a woman goes to the doctor because of new or unusual bleeding from the vagina.

The doctor will ask you about your health and do a physical and a pelvic exam. If signs are pointing to uterine sarcoma, more tests will be ordered. Here are some of the tests you may need:

Endometrial biopsy: For this test, the doctor takes out a small piece of the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) to check it for cancer cells. A very thin tube is put through the vagina into the uterus. Then a small piece of the endometrium is sucked out through the tube. A biopsy is the only way to tell for sure if you have cancer.

Hysteroscopy: A thin long camera is put through the vagina to see into the uterus. The uterus is filled with salt water so the doctor can see it better. This lets the doctor find changes and take out anything (biopsy) that shouldn’t be there. Most times, numbing medicine is used to do this test, but the woman is awake. If a biopsy is done, general anesthesia (where you are asleep) is often used.

Dilation and curettage or D&C: This test might be needed if the biopsy sample doesn't get enough tissue, or the results are not clear. To do this, the opening to the uterus (called the cervix) is opened and a special tool is used to scrape tissue from the endometrium. Drugs are often used to help you sleep during this test.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS): For this test, a small instrument that gives off sound waves and picks up the echoes as they bounce off tissues is put into the vagina. The echoes are made into a picture on a computer screen. These pictures can help see if cancer is growing into the muscle layer of the uterus.

CT scan: This is also called a CAT scan. It’s a special kind of x-ray that takes detailed pictures to see if the cancer has spread.

Chest x-rays: X-rays may be done to see if the cancer has spread to the lungs.

MRI scan: MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays to take detailed pictures. MRIs can be used to learn more about the size of the cancer and if it has spread to other areas of the body.

PET scan: A PET scan uses a special type of sugar that can be seen inside your body with a special camera. The sugar shows up as “hot spots” where the cancer is found. This test can help show if the cancer might have spread.

Protein tests: The cancer cells in the biopsy tissue might be tested for proteins such as the estrogen receptor. Knowing which proteins your cancer has can help the doctor decide if treatments like hormone therapy might help.

Blood tests: Certain blood tests can tell the doctor more about your overall health, like how your kidneys and liver are working.

Questions to ask the doctor

- What tests will I need to have?

- Who will do these tests?

- Where will they be done?

- Who can explain them to me?

- How and when will I get the results?

- Who will explain the results to me?

- What do I need to do next?

How serious is my cancer?

If you have uterine sarcoma, the doctor will want to find out if and how far it has spread. This process is called staging. Your doctor will need to find out the stage of your cancer to help decide what type of treatment is best for you.

The stage describes the growth or spread of the cancer in the place it started. It also tells if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Your cancer can be stage 1, 2, 3, or 4. The lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, like stage 4, means a more serious cancer that has spread from where it started. Be sure to ask about the cancer stage and what it means for you.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Do you know the stage of the cancer?

- If not, how and when will you find out the stage of the cancer?

- Would you explain to me what the stage means for me?

- Based on the stage of the cancer, how long do you think I’ll live?

- What will happen next?

What kind of treatment will I need?

There are many ways to treat uterine sarcoma:

- Surgery and radiation are used to treat only the cancer. They do not affect the rest of the body.

- Chemo, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy drugs go throughout the whole body. They can reach cancer cells almost anywhere in the body.

The treatment plan that’s best for you will depend on:

- Where the cancer is growing

- The stage of the cancer

- The chance that a type of treatment will cure the cancer or help in some way

- Your age

- Other health problems you have

- Your feelings about the treatment and the side effects that come with it

You might get more than one type of treatment. Each treatment has some side effects that can usually be managed or even prevented.

Surgery for uterine sarcoma

Surgery is the most common way to treat early-stage uterine sarcoma. It’s used to take out all the cancer. This means the uterus is removed and this surgery is called a hysterectomy. It can be done in many ways. Sometimes the ovaries and fallopian tubes are taken out at the same time. Nearby lymph nodes might also be taken out to see if they contain cancer cells. Ask your doctor what kind of surgery you will need.

Side effects of surgery

Any type of surgery can have risks and side effects. Ask the doctor what you can expect. If you are having problems after the surgery, let your doctors know. Doctors who treat uterine sarcoma should be able to help you with any problems that come up.

Radiation treatments

Radiation uses high-energy rays (like x-rays) to kill cancer cells. Radiation can be given as the main treatment or after surgery for uterine sarcoma. It can also be used to help with symptoms such as pain, bleeding, or other problems that happen if the cancer has grown very large or has spread to other areas. The main ways radiation can be given are:

- External radiation: Getting this kind of radiation is a lot like getting a regular x-ray, but it takes longer. The radiation is aimed at the cancer from a machine outside the body.

- Vaginal brachytherapy: With this method, radioactive seeds are put into a small tube that’s put in the vagina. Brachytherapy does not affect nearby organs like the bladder or rectum as much as external radiation.

Side effects of radiation treatments

If your doctor suggests radiation treatment, ask what side effects you might have. Side effects depend on the type of radiation that’s used and the part of the body that's treated. The most common side effects of radiation are:

- Skin changes where the radiation is given

- Feeling very tired (fatigue)

- Diarrhea

- Bladder problems

- Scars in the vagina

Most side effects get better after treatment ends. Some might last longer. Talk to your cancer care team about what you can expect.

Chemo

Chemo is short for chemotherapy – the use of drugs to fight cancer. The drugs may be injected through a vein or taken as pills. These drugs go into the blood and spread through most of the body. Chemo is given in cycles or rounds. Each round of treatment is followed by a break. Most of the time, 2 or more chemo drugs are given. Treatment often lasts for many months.

Side effects of chemo

Chemo can make you feel very tired, sick to your stomach, and make your hair fall out. But most chemo side effects go away over time after treatment ends.

There are ways to treat most chemo side effects. If you have side effects, talk to your cancer care team so they can help.

Targeted drug therapy

Targeted drug therapy works differently from chemo drugs. They work against cancer cells by targeting specific parts of cancer cells. Targeted therapy drugs may work even if chemo doesn’t, or they may help chemo work better.

Targeted therapy drugs have different kinds of side effects, so ask your doctor what side effects to expect and how to manage them.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is treatment that either boosts your own immune system or uses man-made versions of parts of the immune system to attack the cancer cells. Immunotherapy drugs are usually given into a vein.

Side effects of immunotherapy

Immunotherapy can cause many different side effects depending on which drug is used. These drugs might make you feel tired, sick to your stomach, or cause a rash. Most of these problems go away after treatment ends.

More serious side effects might happen if the immune system starts attacking normal parts of the body, which can cause serious problems in many organs. You may need to stop the immunotherapy drug and take steroids to treat this side effect.

There are ways to treat most of the side effects caused by immunotherapy. If you have side effects, tell your cancer care team so they can help.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new drugs or other treatments in people. They compare standard treatments with others that may be better.

If you would like to be in a clinical trial, start by asking your doctor if your clinic or hospital conducts clinical trials. See Clinical Trials to learn more.

Clinical trials are one way to get cancer treatments that are being studied for the kind of cancer you have. They are the best way for doctors to find better ways to treat cancer. It’s up to you whether to take part. And if you do sign up for a clinical trial, you can always stop at any time.

What about other treatments I hear about?

When you have cancer you might hear about other ways to treat the cancer or treat your symptoms. These may not always be standard medical treatments. These treatments may be vitamins, herbs, special diets, and other things. You may be curious about these treatments.

Some of these are known to help, but many have not been tested. Some have been shown not to help. A few have even been found to be harmful. Talk to your doctor first if you’re thinking about using or taking anything, whether it’s a vitamin, a diet, or anything else.

Questions to ask the doctor

- What treatment do you think is best for me?

- What's the goal of this treatment? Do you think it could cure the cancer?

- Will treatment include surgery? If so, who will do the surgery?

- What will the surgery be like?

- How will my body work after surgery?

- Will I need other types of treatment, too?

- What's the goal of these treatments?

- Will treatment affect my sex life?

- Will I be able to get pregnant after treatment?

- What side effects could I have from these treatments?

- What can I do about side effects that I might have?

- Is there a clinical trial that might be right for me?

- What about special vitamins or diets that friends tell me about? How will I know if they are safe?

- How soon do I need to start treatment?

- What should I do to be ready for treatment?

- Is there anything I can do to help the treatment work better?

- What's the next step?

What will happen after treatment?

You’ll be glad when treatment is over. But it’s hard not to worry about cancer coming back. Even when cancer never comes back, people still worry about it. For years after treatment ends, you will see your cancer doctor. Be sure to go to all of these follow-up visits. You will have exams, blood tests, and maybe other tests to see if the cancer has come back.

At first, your visits may be every few months. Then, the longer you’re cancer-free, the less often the visits are needed. Scope exams, lab tests, or imaging tests (like MRI or CT scans) may be done to look for signs of cancer or treatment side effects. Your doctor will tell you which tests should be done and how often based on the stage of your cancer and the type of treatment you had.

Having cancer and dealing with treatment can be hard, but it can also be a time to look at your life in new ways. You might be thinking about how to improve your health. Call us at 1-800-227-2345 or talk to your doctor to find out what you can do to feel better.

It is normal to worry when cancer is a part of your life. Some people are affected more than others. But everyone might benefit from help and support from other people, whether friends and family, religious groups, support groups, professional counselors, or others. Learn more in Coping With Cancer.

You can’t change the fact that you have cancer. What you can change is how you live the rest of your life – making healthy choices and feeling as well as you can.

For connecting and sharing during a cancer journey

Anyone with cancer, their caregivers, families, and friends, can benefit from help and support. The American Cancer Society offers the Cancer Survivors Network (CSN), a safe place to connect with others who share similar interests and experiences. We also partner with CaringBridge, a free online tool that helps people dealing with illnesses like cancer stay in touch with their friends, family members, and support network by creating their own personal page where they share their journey and health updates.

- Written by

- Words to know

- How can I learn more?

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

Biopsy (BY-op-see): Taking out a small piece of tissue to see if there are cancer cells in it.

Endometrium (en-doe-ME-tree-um): The lining of the womb (uterus).

Fallopian (fuh-LO-pee-in) tube: the tube that carries an egg from the ovary to the uterus. There are 2 of them.

Lymph nodes (limf nodes): Small, bean-shaped sacs of immune system tissue found all over the body and connected by lymph vessels; also called lymph glands.

Metastasis (muh-TAS-tuh-sis): Cancer cells that have spread from where they started to other places in the body.

Myometrium (my-o-ME-tree-um): The thick muscle layer or the uterus that's needed to push a baby out during childbirth.

Ovary (O-vuh-ree): Reproductive organ in the female pelvis. Normally a woman has 2 ovaries. They contain the eggs (ova) that, when joined with sperm, can result in pregnancy.

Sarcoma (sar-KO-muh): Cancer that starts in connective tissue, such as cartilage, fat, muscle, or bone.

Uterus (YEW-tuh-rus): Also called the womb. The pear-shaped organ in a woman’s pelvis that holds a growing baby.

Vagina (vuh-JIE-nuh): The passage leading from the vulva (the female genital organs that are on the outside of the body) to the uterus (the womb).

We have a lot more information for you. You can find it online at www.cancer.org. Or, you can call our toll-free number at 1-800-227-2345 to talk to one of our cancer information specialists.

Last Revised: September 20, 2022

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.