Your gift is 100% tax deductible.

What Is Endometrial Cancer?

Endometrial cancer starts when cells in the endometrium (the inner lining of the uterus) begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer, and can spread to other parts of the body.

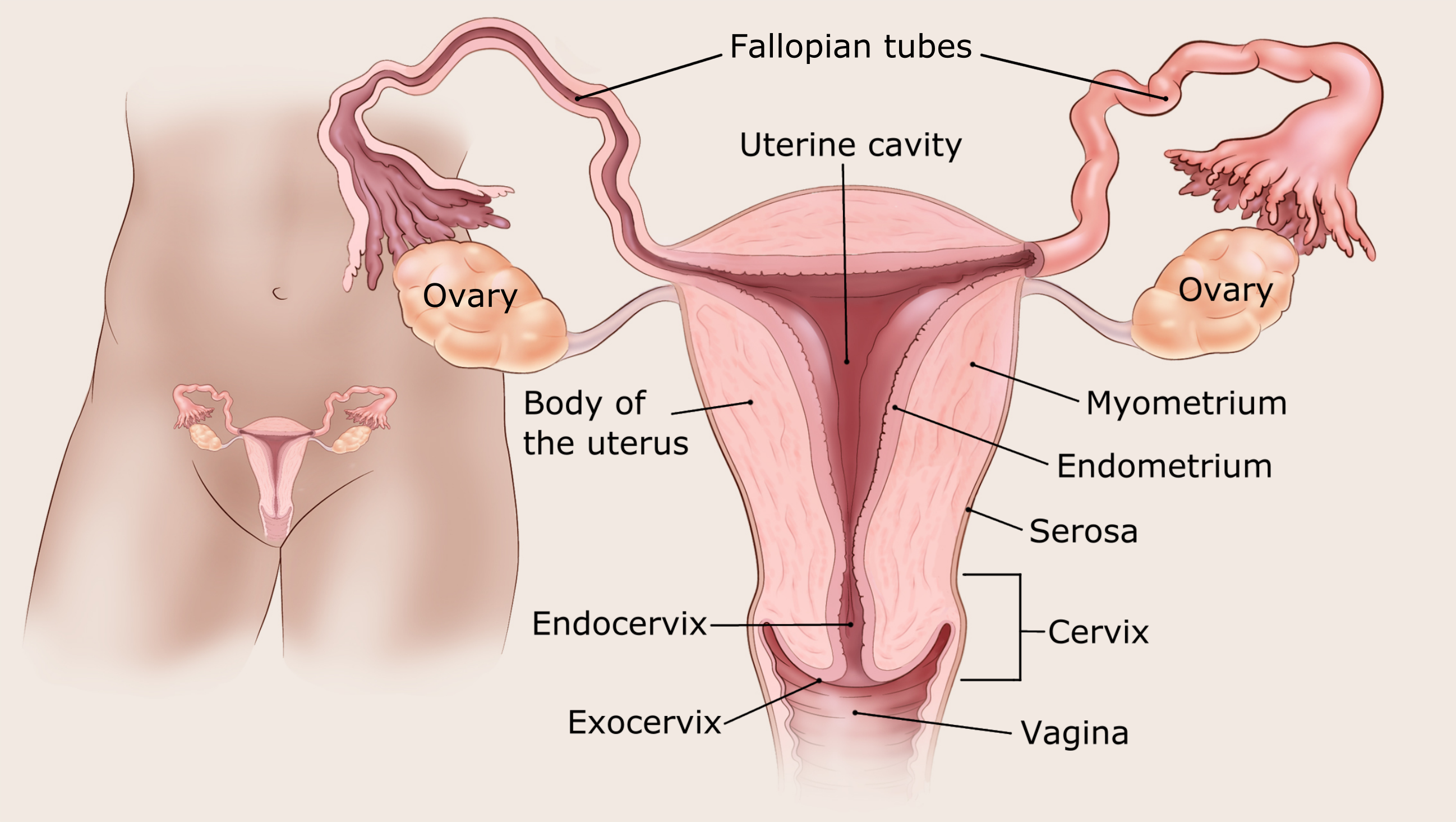

About the uterus and endometrium

The uterus is a hollow organ, normally about the size and shape of a medium-sized pear. The uterus is where a fetus grows and develops during pregnancy. During childbearing years, the body's ovaries typically release an egg every month, and hormones cause the lining of the endometrium to grow and thicken in preparation for pregnancy. If pregnancy doesn't occur, this endometrial lining sheds through the vagina, a process known as menstruation. This process continues to occur each month until menopause, when the ovaries stop releasing eggs and producing female hormones.

The uterus has 3 sections:

- The cervix, which is the narrow lower section

- The isthmus, which is the broad section (or the body of the uterus) in the middle

- The fundus, which is the dome-shaped top section

When people talk about uterine cancer, they usually mean cancers that start in the body of the uterus, not the cervix. (Cervical cancer is a different type of cancer.)

The body of the uterus has 3 main layers:

- The myometrium is the outer layer. This thick layer of muscle is needed to push the baby out during birth.

- The endometrium is the inner layer.

- The serosa which coats the outside of the uterus.

Types of endometrial cancer (WHO classification)

Endometrial carcinomas

Endometrial cancer (also called endometrial carcinoma) starts in the cells of the inner lining of the uterus (the endometrium). This is the most common type of uterine cancer.

Endometrial carcinomas are classified by how the cells look under the microscope. These are called histologic types and are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO); They include:

- Endometrioid carcinoma

- Serous carcinoma

- Clear cell carcinoma

- Undifferentiated carcinoma/ Dedifferentiated carcinoma

- Mixed carcinoma

- Carcinosarcoma

- Rare/other endometrial carcinomas

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Most endometrial cancers are adenocarcinomas. Endometrioid carcinoma is the most common type of adenocarcinoma. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma start in gland cells and look a lot like the normal uterine lining (endometrium).

Other types of uterine cancers

Uterine carcinosarcoma (CS) starts in the endometrium and has features of both endometrial carcinoma and sarcoma. A sarcoma is a cancer that starts in muscle cells of the uterus. In the past, CS was considered a different type of uterine cancer called uterine sarcoma (see below), but doctors now believe that uterine CS is an endometrial carcinoma that's has grown so abnormally that it no longer looks like the cells from which it came, the endometrium. Uterine CS are also known as malignant mixed mesodermal tumors or malignant mixed mullerian tumors (MMMTs). They make up about 3% of uterine cancers.

Uterine sarcomas start in the muscle layer (myometrium) or supporting connective tissue of the uterus. These include uterine leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas. These cancers are not covered here but are discussed in detail in Uterine Sarcoma.

Cancers that start in the cervix and then spread to the uterus are different from cancers that start in the body of the uterus. They're described in Cervical Cancer.

Estrogen-dependent endometrial cancers (traditional classification)

Endometrial cancers were traditionally categorized into two types, based on whether the cancer cells are dependent on estrogen.

Type 1 endometrial cancers are the most common type. They are mostly endometrioid adenocarcinomas and depend on estrogen for growth. Type 1 cancers are usually not very aggressive and don't spread to other tissues quickly. They sometimes develop from atypical hyperplasia, an abnormal overgrowth of cells in the endometrium. (See Endometrial Cancer Risk for more on this.)

Type 2 endometrial cancers are mostly serous carcinomas and do not depend on estrogen for growth. These types of cancers have poorer outlook compared to Type 1. Doctors tend to treat these cancers more aggressively.

Endometrial cancers classified by grade

Endometrial cancer also is given a grade based the percentage of cancer cells present. Cancer cells are identified when the pathologist sees a solid non-glandular growth.

The lower-grade cancers are grades 1 and 2 endometrial cancers. The higher-grade cancers are grade 3 endometrial cancer, as well as all serous adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, mixed carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas.

- Grade 1 tumors have 5% or less than 5% of tumor cells present in their sample.

- Grade 2 tumors have 6% to 50% tumor cells present.

- Grade 3 tumors have greater than 50% tumor cells present. Grade 3 cancers tend to be aggressive (they grow and spread fast) and have a worse outlook than lower-grade cancers.

Molecular classification of endometrial cancers

In addition to the WHO classification, endometrial cancers can be further classified into molecular subtypes. Assigning an endometrial cancer into a particular molecular sub-type is based on the mutation found in a cancer cell. Identification of the specific subtype of endometrial cancer can help doctors understand the likelihood of the cancer recurring after treatment, and as well which treatment would be most effective. There are 4 molecular subtypes of endometrial cancer:

- DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE)-mutated

- Mismatch repair-deficient

- No specific molecular profile

- P53 abnormal

Noncancerous conditions of the endometrium

A tumor can be cancerous or benign. A cancerous tumor is malignant, meaning it can grow and spread to other parts of the body. A benign tumor can grow but generally will not spread to other body parts.

Benign conditions of the endometrium include:

- Fibroids (tumors in the muscle of the uterus)

- Polyps (abnormal growths in the lining of the uterus)

- Endometriosis (a condition in which endometrial tissue, which usually lines the inside of the uterus, is found on the outside of the uterus or other organs)

- Endometrial hyperplasia: A condition in which there is an increased number of cells and glandular structures in the uterine lining. Endometrial hyperplasia can have either normal or abnormal cells and simple or complex glandular structures. The risk for developing cancer in the lining of the uterus is higher when endometrial hyperplasia has atypical cells and complex glands.

- Written by

- References

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983 Feb;15(1):10-17.

Crosbie EJ, Kitson SJ, McAlpine JN, Mukhopadhyay A, Powell ME, Singh N. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2022 Apr 9;399(10333):1412-1428.

Mahdy H, Casey MJ, Vadakekut ES, Crotzer D. Endometrial Cancer. 2024 Apr 20. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL)

Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983 Feb;15(1):10-7.

Crosbie EJ, Kitson SJ, McAlpine JN, Mukhopadhyay A, Powell ME, Singh N. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2022 Apr 9;399(10333):1412-1428.

Mahdy H, Casey MJ, Vadakekut ES, Crotzer D. Endometrial Cancer. 2024 Apr 20. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL).

National Cancer Institute. Endometrial Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. February 8, 2024. Accessed at www.cancer.gov/types/uterine/hp/endometrial-treatment-pdq/#section/all on July 17, 2024.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Uterine Neoplasms, Version 2.2024. March 6, 2024. Accessed at www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf on July 17, 2024.

Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, McCann SE, Yu H, Xiang YB, Australian National Endometrial Cancer Study Group; et al . Type I and II endometrial cancers: Have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jul 10;31(20):2607-18.

Soslow RA, Tornos C, Park KJ, Malpica A, Matias-Guiu X, Oliva E, et al. Endometrial Carcinoma Diagnosis: Use of FIGO Grading and Genomic Subcategories in Clinical Practice: Recommendations of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019 Jan;38 Suppl 1(Iss 1 Suppl 1):S64-S74.

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed, IARC, 2020. Vol 4.

Last Revised: February 28, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.