If Your Child Has a Wilms Tumor

If your child has been diagnosed with a Wilms tumor, this guide can give you more information.

What are Wilms tumors?

Wilms tumors are a type of kidney cancer that is most often found in young children. These tumors can also happen in older children, or even teens or adults, but this is rare.

Cancer of any kind starts when cells in the body begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer. Wilms tumors start in one or both kidneys.

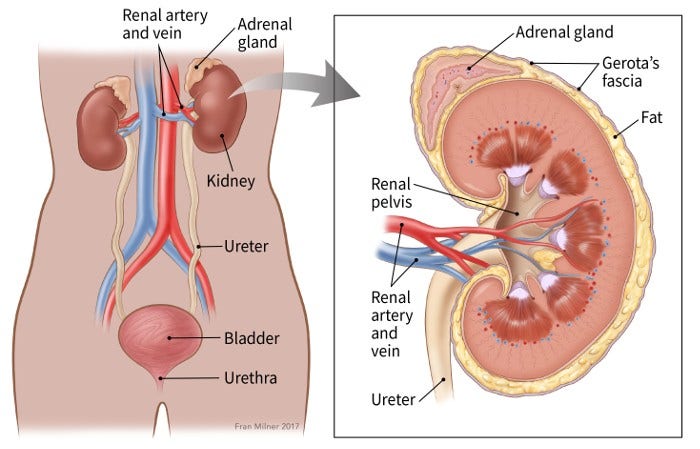

To understand Wilms tumors, it helps to know about the kidneys and how they work. The kidneys are 2 bean-shaped organs attached to the back wall of the abdomen (see picture). One kidney is just to the left and the other just to the right of the backbone.

The kidneys do a number of things:

- They filter the blood to remove excess water, salt, and waste products, which leave the body as urine.

- They help control blood pressure.

- They help make sure the body has enough red blood cells.

Our kidneys are important, but we need less than one complete kidney to do all of its basic functions.

Most often, Wilms tumors happen in only one kidney. But a small number of children have tumors in both kidneys.

Types of Wilms tumors

There are two major types of Wilms tumors. These are grouped based on how they look under a microscope (called their histology):

- Favorable: The cancer cells in these tumors don’t look quite normal, but they don’t look very abnormal, either. Most Wilms tumors have a favorable histology. The chance of curing children with these tumors is very good.

- Anaplastic: In these tumors, the look of the cancer cells varies widely, and parts of the cell tend to be very large and distorted. This is called anaplasia. Anaplasia can be either focal (limited to just certain parts of the tumor) or diffuse (spread widely through the tumor).

Questions to ask the doctor

- How sure are you that my child has a Wilms tumor?

- Is there a chance it’s not a Wilms tumor?

- Would you please write down the kind of tumor you think my child has?

- What will happen next?

How does the doctor know my child has a Wilms tumor?

Wilms tumors often grow quite large before causing any symptoms. The first symptom of a Wilms tumor is usually swelling or hardness in the belly. This might happen on one side or both. It’s usually not painful.

Other symptoms of Wilms tumor might include:

- Fever

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Shortness of breath

- Constipation

- Blood in the urine

Wilms tumors can also sometimes cause high blood pressure. This might not cause symptoms on its own. But in rare situations a child’s blood pressure might get high enough to cause problems like headaches, bleeding inside the eye, or even a change in consciousness.

If your child has symptoms that could be from a Wilms tumor, the doctor will want to get a complete medical history to find out more about the symptoms. They will also do a physical exam. Tests might be needed as well.

Tests that may be done

Here are some of the tests for a Wilms tumor your child may need:

Ultrasound: This is often the first test done if the doctor thinks your child has a tumor in their belly. This test does not use radiation, and it gives the doctor a good view of the kidneys and the other organs in the belly.

CT or CAT scan: This test uses x-rays to make detailed pictures of the inside of the body. It is one of the most useful tests to look for a tumor inside the kidney. It can also show if the cancer has grown into nearby veins or spread to other organs, like the lungs.

MRI: This test uses radio waves and strong magnets to make detailed pictures of the inside of the body. It might be done if the doctor needs to see very detailed pictures of your child’s kidney or nearby areas.

Chest x-ray: This test might be done to look for spread of Wilms tumor to the lungs. A chest x-ray isn’t needed if a CT scan of the chest is done.

Lab tests: Blood and urine tests might be done if your child’s doctor suspects a kidney problem. These tests might also be done after a Wilms tumor has been found.

Biopsy: The tests listed above give doctors a lot of information. Most of the time, this is enough to decide if your child most likely has a Wilms tumor, and therefore needs surgery. But to know for sure, a piece of the tumor must be removed and checked under a microscope.

This is most often done as part of the surgery to treat the tumor. But sometimes a small piece of the tumor is removed during a biopsy, before surgery. This might happen if the doctors are less sure about the diagnosis, or if they aren’t sure all of the tumor can be removed.

Questions to ask the doctor

- What tests will my child need?

- Who will do these tests?

- Where will they be done?

- Who can explain them to us?

- How and when will we get the results?

- Who will explain the results to us?

- What do we need to do next?

How serious is my child’s Wilms tumor?

If your child has a Wilms tumor, the doctor will want to find out some key pieces of information to help decide how to treat it. The most important information is:

- The stage (extent) of the Wilms tumor. This depends on whether the tumor is in one kidney or both, if it has grown outside the kidney, and if all of it can be removed with surgery.

- The histology of the tumor (favorable or anaplastic).

Doctors also use other information as they decide on treatment options and a child’s chances of getting better. This includes:

- The child’s age

- If the tumor cells have certain gene changes

- The size of the tumor

Doctors use all this information to put a child with a Wilms tumor into a risk group. Risk groups help doctors decide how best to treat a child.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Where exactly is my child’s tumor?

- How big is the tumor?

- Can all of it be removed?

- Has it spread anywhere else?

- What is the stage of the tumor?

- What is the histology of the tumor? What does this mean?

- Which risk group is my child in?

- How do these things affect our treatment options?

- What will happen next?

What kind of treatment will my child need?

The main treatments for Wilms tumors are:

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy (chemo)

- Radiation treatment

Surgery

In the United States, surgery is the first treatment for most children with Wilms tumors. The main goal is to remove the entire Wilms tumor in one piece, if possible. If this can’t be done safely, then other treatments like chemo might be done first to shrink the tumor and make surgery easier.

The main operations to treat Wilms tumors are:

Radical nephrectomy: This surgery removes the entire kidney and some nearby structures. It is the most common surgery if a Wilms tumor is only in one kidney, as it gives the best chance of making sure all of the tumor is removed.

Partial nephrectomy (nephron-sparing surgery): This surgery removes only part of the kidney(s). It is used most often in children who have Wilms tumors in both kidneys. This is done to try to save some normal kidney tissue.

Ask your cancer care team what type of surgery your child needs and what to expect.

Central venous catheter (CVC) or port

If your child is going to get chemo, a surgeon might insert a small tube into a large blood vessel, usually under the collar bone. This tube is called a central venous catheter (CVC) or a port.

It might be placed during the surgery to remove the tumor, or as a separate operation (if chemo is going to be given before the surgery).

Side effects of surgery

Any type of surgery can have risks and side effects, such as bleeding or infections. Ask your child’s cancer care team what to expect. If your child has any problems, let them know.

Doctors and nurses who treat children with Wilms tumors should be able to help you with any problems that come up.

Most children do well if only one kidney is removed. But children who have both kidneys removed, or even parts of both kidneys removed, might need regular dialysis treatments to filter their blood. They also might need a kidney transplant at some point.

Chemo

Chemotherapy (chemo) is the use of drugs to fight cancer. These drugs are put into the blood and spread through the body.

Most children with Wilms tumors will get chemo at some point during their treatment. (Some children with very low risk tumors might not need it.)

Chemo is usually given after surgery, but sometimes it’s given before surgery to shrink the tumor and make the surgery easier.

Children with Wilms tumors will get 2 or more chemo drugs as part of their treatment. Chemo is given in cycles or rounds. Each round of treatment is followed by a break. Treatment often lasts for many months.

Side effects of chemo

Chemo can make your child feel very tired and sick to their stomach. It can also make their hair fall out. It might cause other problems, too. These problems tend to go away after treatment ends, but chemo sometimes has long-term side effects.

There are ways to treat most chemo side effects. If your child has side effects, talk to the cancer care team so they can help.

Radiation therapy

Radiation uses high-energy rays (like x-rays) to kill cancer cells. It may be used:

- After surgery to kill any tumor cells left behind

- Before surgery to try to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove

- As the part of the main treatment if surgery can’t be done

For Wilms tumors, radiation is aimed at the tumor from a machine outside the body. Most often it’s given 5 days a week for at least a few weeks. Radiation is a lot like getting an x-ray. The radiation is stronger than an x-ray, but your child will not feel it. Each treatment takes about 15 to 30 minutes.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation might cause some children to feel tired. They might also feel sick and throw up. A child might also have loose stools (diarrhea). Radiation can also affect the skin where it enters the body. This can cause changes that are like a sunburn.

Most of these side effects get better after treatment ends, but some side effects might last longer. Other side effects might not show up until years later.

Talk to your child’s cancer care team about what to expect during and after treatment. There may be ways to ease some side effects.

Clinical trials

Most children with Wilms tumors are treated while on a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies that test new drugs or other treatments in people. They compare standard treatments with others that may be better.

Clinical trials are one way to get the newest treatments. They are the best way for doctors to find better ways to treat cancer. Still, they might not be right for everyone. If your child’s cancer care team talks to you about a clinical trial, it’s up to you whether to take part.

If you would like to learn more about clinical trials that might be right for your child, start by asking the cancer care team. See Clinical Trials to learn more.

What about other treatments I hear about?

When your child has a Wilms tumor, you might hear about other ways to treat it or treat symptoms from it. These may not always be standard medical treatments. These treatments may be vitamins, herbs, diets, and other things.

Some of these might help, but many have not been tested. Some have been shown not to help. A few have even been found to be harmful. Talk to your child’s cancer care team about anything you’re thinking about using, whether it’s a vitamin, a diet, or anything else.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Do we need any other tests before we can decide on treatment?

- What treatment do you think is best for my child?

- What’s the goal of this treatment? How likely is it to cure the tumor?

- Will treatment include surgery? If so, who will do the surgery?

- What will the surgery be like?

- Will my child need other types of treatment, too?

- What will these treatments be like?

- What’s the goal of these treatments?

- What side effects could my child have from these treatments?

- What can we do about these side effects?

- Is there a clinical trial that might be right for my child?

- What about vitamins or diets that friends tell me about? How will we know if they are safe?

- How soon do we need to start treatment?

- What should we do to be ready for treatment?

- Is there anything we can do to help the treatment work better?

- What’s the next step?

What will happen after treatment?

You’ll probably be glad when treatment is over. But it can be hard not to worry about the tumor coming back. Even if it never comes back, you (and your child) might still worry about it.

For years after treatment ends, your child will still need to see the doctor. At first, these visits may be every few months. The longer your child is cancer-free, the less often they will need to visit the doctor.

Be sure your child goes to all of their follow-up visits.

During these visits, the cancer care team will ask about symptoms, do physical exams, and maybe do tests to see if the tumor has come back. They may also test to see if the cancer or its treatment has caused any long-term problems. If needed, they will help you and your child learn to deal with the changes.

Learn more in What Happens After Treatment for a Wilms Tumor.

For connecting and sharing during a cancer journey

Anyone with cancer, their caregivers, families, and friends, can benefit from help and support. The American Cancer Society offers the Cancer Survivors Network (CSN), a safe place to connect with others who share similar interests and experiences. We also partner with CaringBridge, a free online tool that helps people dealing with illnesses like cancer stay in touch with their friends, family members, and support network by creating their own personal page where they share their journey and health updates.

- Written by

- Words to know

- How can I learn more?

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Biopsy (BY-op-see): Taking out a piece of an abnormal area to see if there are cancer cells in it.

Central venous catheter (CVC): A small tube that is put into a large blood vessel (usually under the collar bone). One end stays outside of the body or just under the skin. It can be left in place for months and can be used to give chemo or take blood samples. Also called a venous access device (VAD) or a port.

Chemotherapy (KEY-mo-THAIR-uh-pee): The use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Also called chemo.

Metastasis (muh-TAS-tuh-sis): The spread of cancer cells from where they started to other places in the body.

Nephrectomy (nef-REK-tuh-mee): Surgery to remove a kidney (radical nephrectomy) or part of a kidney (partial nephrectomy).

Radiation (ray-dee-AY-shun) therapy: The use of high-energy rays (like x-rays) to kill cancer cells.

We have a lot more information for you. You can find it online at www.cancer.org. Or, you can call our toll-free number at 1-800-227-2345 to talk to one of our cancer information specialists.

Last Revised: January 21, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.