Your gift is 100% tax deductible

Screening Tests for Prostate Cancer

Screening is testing to find cancer in people before they have symptoms. At this time, it’s not clear if the benefits of prostate cancer screening outweigh the risks for most men. Still, after discussing the pros and cons of screening with their doctors, some men might reasonably choose to be screened.

The screening tests discussed here can be used to look for possible signs of prostate cancer. But these tests can’t tell for sure if you have cancer. If the result of one of these tests is abnormal, you will probably need a prostate biopsy (discussed below) to know for sure if you have cancer.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein made by cells in the prostate gland (both normal cells and cancer cells). PSA is mostly in semen, but a small amount is also found in the blood.

The PSA level in blood is measured in units called nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). The chance of having prostate cancer goes up as the PSA level goes up, but there is no set cutoff point that can tell for sure if a man does or doesn’t have prostate cancer.

Many doctors use a PSA cutoff point of 4 ng/mL or higher when deciding if a man might need further testing, while others might recommend it starting at a lower level, such as 2.5 or 3. And some doctors might use age-specific cutoffs (see “Special types of PSA tests,” below).

- Most men without prostate cancer have PSA levels under 4 ng/mL of blood. When prostate cancer develops, the PSA level often goes above 4. Still, a level below 4 is not a guarantee that a man doesn’t have cancer. About 15% of men with a PSA below 4 will have prostate cancer if a biopsy is done

- Men with a PSA level between 4 and 10 (often called the “borderline range”) have about a 1 in 4 chance of having prostate cancer.

- If the PSA is more than 10, the chance of having prostate cancer is over 50%.

If your PSA level is high, you might need further tests to look for prostate cancer (see “If screening test results aren’t normal,” below).

Other factors that might affect PSA levels

One reason it’s hard to use a set cutoff point with the screening PSA test is that factors other than cancer can also affect PSA levels.

Factors that might raise PSA levels include:

- Older age: PSA levels normally go up slowly as you get older, even if your prostate is normal.

- Having an enlarged prostate: Conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate that affects many men as they grow older, can raise PSA levels.

- Prostatitis: This is an infection or inflammation of the prostate gland, which can raise PSA levels.

- Ejaculation: This can make the PSA go up for a short time. This is why some doctors suggest that men abstain from ejaculation for a day or two before testing.

- Riding a bicycle: Some studies have suggested that cycling may raise PSA levels for a short time (possibly because the seat puts pressure on the prostate), although not all studies have found this.

- Certain urologic procedures: Some procedures done in a doctor’s office that affect the prostate, such as a prostate biopsy or cystoscopy, can raise PSA levels for a short time. Some studies have suggested that a digital rectal exam (DRE) might raise PSA levels slightly, although other studies have not found this. Still, if both a PSA test and a DRE are being done during a doctor visit, some doctors advise having the blood drawn for the PSA before having the DRE, just in case.

- Certain medicines: Taking male hormones like testosterone (or other medicines that raise testosterone levels) may cause a rise in PSA.

Some things might lower PSA levels (even if a man has prostate cancer):

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: Certain drugs used to treat BPH or urinary symptoms, such as finasteride (Proscar or Propecia) or dutasteride (Avodart), can lower PSA levels. These drugs can also affect prostate cancer risk (discussed in Can Prostate Cancer Be Prevented?. Tell your doctor if you are taking one of these medicines. Because they can lower PSA levels, the doctor might need to adjust for this.

- Herbal mixtures: Some mixtures that are sold as dietary supplements might mask a high PSA level. This is why it’s important to let your doctor know if you are taking any type of supplement, even ones that are not necessarily meant for prostate health. Saw palmetto (an herb used by some men to treat BPH) does not seem to affect PSA.

- Certain other medicines: Some research has suggested that long-term use of certain medicines, such as aspirin, statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs), and thiazide diuretics (such as hydrochlorothiazide) might lower PSA levels. More research is needed to confirm these findings.

For men who are thinking about being screened for prostate cancer, it’s important to talk to your doctor about anything you’re taking that might affect your PSA level, as it might affect the accuracy of your test result.

A word about at-home PSA tests

Some companies now offer PSA test kits that let you collect a blood sample at home (typically from a finger stick) and then send it to a lab for testing. This could be more convenient for some men, and it might even allow some men to be tested who otherwise might not be.

However, a drawback with at-home testing is that it might not give a man the chance to discuss the pros and cons of prostate cancer screening with a health care provider before being tested, which could help him make an informed decision on whether to be screened. This shared decision making is an important part of the American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection.

Another important issue is that PSA blood test results are not black and white – that is, the test can’t tell for sure that you have (or don’t have) prostate cancer. It’s important to discuss the test results with a health professional who understands what the results mean for you.

Special types of PSA tests

The PSA level from a screening test is sometimes referred to as total PSA, because it includes all forms of PSA (described below). If you decide to get a PSA screening test and the result isn’t normal, some doctors might consider using different types of PSA tests to help decide if you need a prostate biopsy, although not all doctors agree on how to use these tests. If your PSA test result isn’t normal, ask your doctor about what it means for your prostate cancer risk and your need for further tests.

Percent-free PSA: PSA occurs in 2 major forms in the blood. One form is attached (“complexed”) to blood proteins, while the other circulates free (unattached). The percent-free PSA (%fPSA), also known as the free/total PSA ratio (f/t PSA), is the ratio of how much PSA circulates free compared to the total PSA level. The percent-free PSA is lower in men who have prostate cancer than in men who do not.

If your PSA test result is in the borderline range (between 4 and 10), the percent-free PSA might be used to help decide if you should have a prostate biopsy. A lower percent-free PSA means that your chance of having prostate cancer is higher and you should probably have a biopsy.

Many doctors recommend a prostate biopsy for men whose percent-free PSA is 10% or less, and advise that men consider a biopsy if it is between 10% and 25%. Using these cutoffs detects most cancers and helps some men avoid unnecessary biopsies. This test is widely used, but not all doctors agree that 25% is the best cutoff point to decide on a biopsy, and the cutoff may change depending on the overall PSA level.

Complexed PSA: This test directly measures the amount of PSA that is attached to other proteins (the portion of PSA that is not “free”). This test could be done instead of checking the total and free PSA, and it could give the same amount of information, but it is not widely used.

Tests that combine different types of PSA: Some newer tests combine the results of different types of PSA to get an overall score that reflects the chance a man has prostate cancer (particularly cancer that might need treatment). These tests include:

- The Prostate Health Index (PHI), which combines the results of total PSA, free PSA, and proPSA

- The 4Kscore test, which combines the results of total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and human kallikrein 2 (hK2), along with some other factors

- The IsoPSA test, which looks at different forms of PSA proteins in the blood to help determine if they came from cancer cells

These tests might be useful in men with a slightly elevated PSA, to help determine if they should have a prostate biopsy. Some of these tests might also be used to help determine if a man who has already had a prostate biopsy that didn’t find cancer should have another biopsy.

PSA velocity: The PSA velocity is not a separate test. It is a measure of how fast the PSA rises over time. Normally, PSA levels go up slowly with age. Some research has found that these levels go up faster if a man has cancer, but studies have not shown that the PSA velocity is more helpful than the PSA level itself in finding prostate cancer. For this reason, most doctors do not use PSA velocity as part of screening for prostate cancer.

PSA density: PSA levels are higher in men with larger prostate glands. The PSA density (PSAD) is sometimes used for men with large prostate glands to try to adjust for this. The doctor measures the volume (size) of the prostate gland with transrectal ultrasound (TRUS, discussed in Tests to Diagnose and Stage Prostate Cancer) and divides the PSA number by the prostate volume. A higher PSA density indicates a greater likelihood of cancer. PSA density appears to be about as accurate as the percent-free PSA test, although a drawback is that it requires that an ultrasound is done.

Age-specific PSA ranges: PSA levels are normally higher in older men than in younger men, even when there is no cancer. A PSA result within the borderline range might be more worrisome in a 50-year-old man than in an 80-year-old man. For this reason, some doctors have suggested comparing PSA results with results from other men of the same age. But the usefulness of age-specific PSA ranges is not well proven, so most doctors and professional organizations do not recommend their use at this time.

Digital rectal exam (DRE)

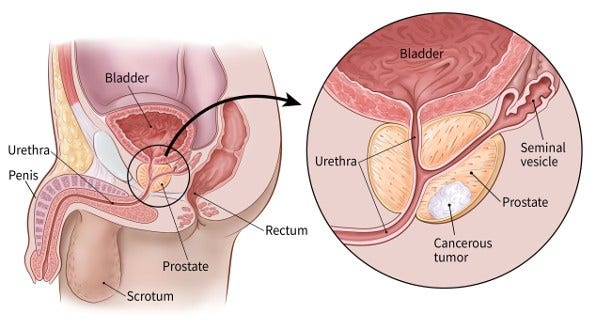

For a digital rectal exam (DRE), the doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum to feel for any bumps or hard areas on the prostate that might be cancer. As shown in the picture below, the prostate is just in front of the rectum. Prostate cancers often begin in the back part of the gland, and can sometimes be felt during a rectal exam. This exam can be uncomfortable (especially for men who have hemorrhoids), but it usually isn’t painful and only takes a short time.

DRE is less effective than the PSA blood test in finding prostate cancer, but it can sometimes find cancers in men with normal PSA levels. For this reason, it might be included as a part of prostate cancer screening.

If screening test results aren’t normal

If you are screened for prostate cancer and your initial blood PSA level is higher than normal, it doesn’t always mean that you have prostate cancer. Many men with higher-than-normal PSA levels do not have cancer. Still, further testing will be needed to help find out what is going on. Your doctor may advise one of these options:

- Waiting a while and having a second PSA test

- Getting another type of test to get a better idea of if you might have cancer (and therefore should get a prostate biopsy)

- Getting a prostate biopsy to find out if you have cancer

It’s important to discuss your options, including their possible pros and cons, with your doctor to help you choose one you are comfortable with. Factors that might affect which option is best for you include:

- Your age and overall health

- The likelihood that you have prostate cancer (based on tests done so far)

- Your own comfort level with waiting or getting further tests

If your initial PSA test was ordered by your primary care provider, you may be referred to a urologist (a doctor who treats diseases of the genital and urinary tract, including prostate cancer) for this discussion or for further testing.

Repeating the PSA test

A man’s blood PSA level can vary over time (for a number of reasons), so some doctors recommend repeating the test after a month or so if the initial PSA result is abnormal. This is most likely to be a reasonable option if the PSA level is on the lower end of the borderline range (typically 4 to 7 ng/mL). For higher PSA levels, doctors are more likely to recommend getting other tests, or going straight to a prostate biopsy.

Getting other tests

If the initial PSA result is abnormal, another option might be to get another type of test (or tests) to help you and your doctor get a better idea if you might have prostate cancer (and therefore need a biopsy). Some of the tests that might be done include:

- A digital rectal exam (DRE), if it hasn’t been done already

- One or more of the other special types of PSA tests discussed above, such as the Prostate Health Index (PHI), 4Kscore test, IsoPSA, or percent-free PSA; or other lab tests, such as the ExoDx Prostate(IntelliScore) or SelectMDx (described in What’s New in Prostate Cancer Research?)

- An imaging test of the prostate gland, such as MRI (especially multiparametric MRI) or transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) (discussed in Tests to Diagnose and Stage Prostate Cancer)

If the initial abnormal test was a DRE, the next step is typically to get a PSA blood test (and possibly other tests, such as a TRUS).

Getting a prostate biopsy

For some men, getting a prostate biopsy might be the best option, especially if their initial PSA level is high. A biopsy is a procedure in which small samples of the prostate are removed and looked at under a microscope. This test is the only way to know for sure if a man has prostate cancer. If prostate cancer is found on a biopsy, this test can also help tell how likely it is that the cancer will grow and spread quickly.

For more details on the prostate biopsy and how it is done, see Tests to Diagnose and Stage Prostate Cancer

- Written by

- References

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

Chang SL, Harshman LC, Presti JC Jr. Impact of common medications on serum total prostate-specific antigen levels: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3951-3957.

Freedland S. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen. UpToDate. 2023. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/measurement-of-prostate-specific-antigen on July 10, 2023.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection. Version 1.2023. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf on July 10, 2023.

National Cancer Institute. Physician Data Query (PDQ). Prostate Cancer Screening. 2023. Accessed at https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/hp/prostate-screening-pdq on July 10, 2023.

Olleik G, Kassouf W, Aprikian A, et al. Evaluation of new tests and interventions for prostate cancer management: A systematic review. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(11):1340-1351.

Preston MA. Screening for prostate cancer. UpToDate. 2023. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-prostate-cancer on July 10, 2023.

Last Revised: November 22, 2023

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.