ACS Research News

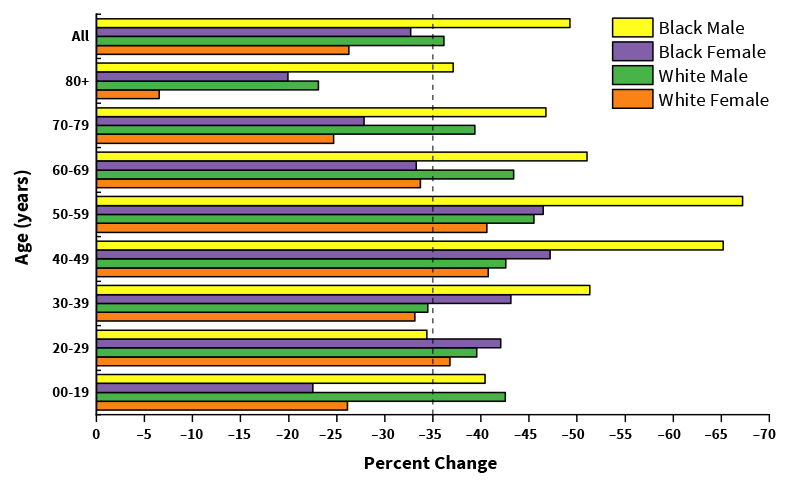

New Study Calls for Action to Reverse Course of Racial Disparities

Published on: February 24, 2025

Stark racial inequities in cancer incidence and survival spur the need for scientists, clinicians, and policymakers to unite and drive for meaningful change.

Spotlight: New Mission Boost and Discovery Boost Grants

Published on: January 23, 2025

In the Fall 2024 grant cycle, American Cancer Society invests more than $12 million in new exploratory and translational grants.

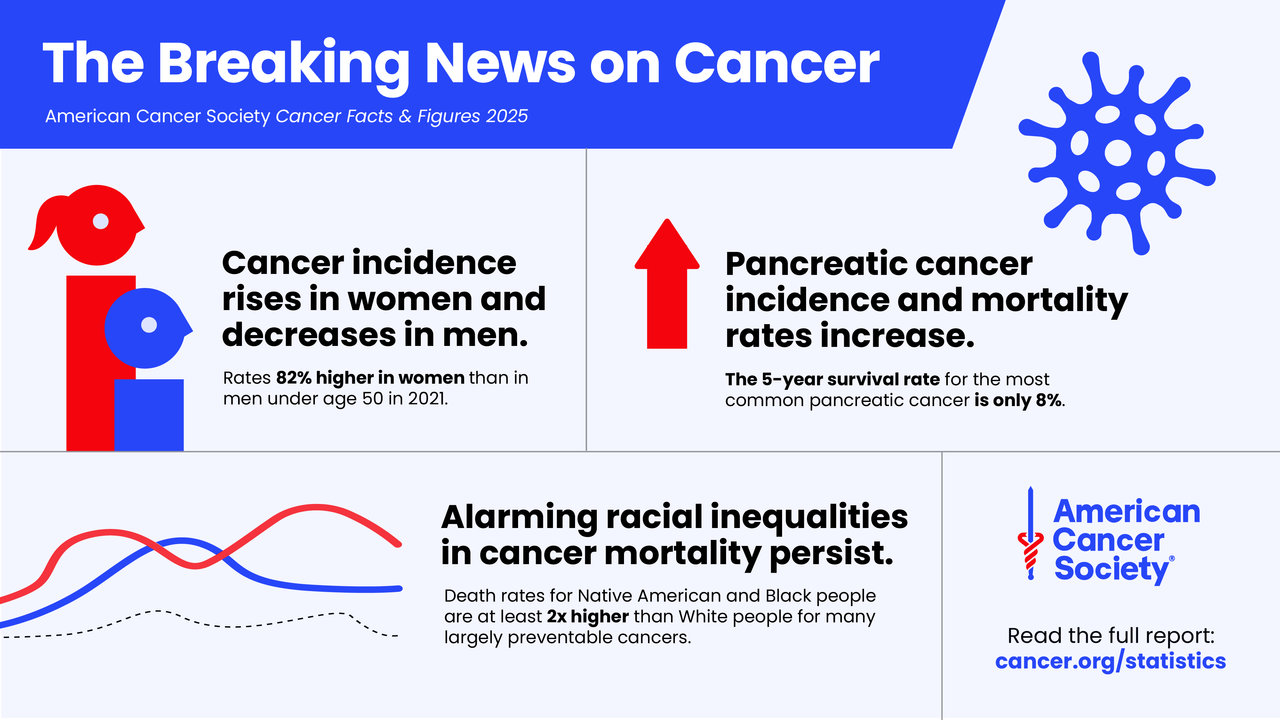

Cancer Incidence Rate for Women Under 50 Rises Above Men's

Published on: January 16, 2025

The American Cancer Society 2025 statistics publications show how the cancer incidence rate in women younger than age 50 surpasses men’s.

American Cancer Society Mentored Grantee Highlights from the Newly Announced Fall 2024 Grant Slate

Published on: January 13, 2025

American Cancer Society highlights several of the stand-out projects from mentored grantees that are part of the larger Fall 2024 grant slate.