Breast Cancer Death Rates Are Highest for Black Women—Again

ACS researchers report and explain statistics about breast cancer in a new article in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians and in Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2022-2024.

A new American Cancer Society (ACS) report finds that the death rate for breast cancer in the United States among women dropped 43% between 1989 when it peaked and 2020. During the last decade, death rates declined similarly for women of all racial/ethnic groups across the US except for American Indians/Alaska Natives (AIANs), who had stable rates. However, Black women are still more likely to die from breast cancer than White women across the US, even though Black women have lower breast cancer incidence rates.

We have been reporting this same disparity year after year for a decade. The differences in death rates are not explained by Black women having more aggressive cancers. It is time for health systems to take a hard look at how they are caring differently for Black women.”

These findings are published in “Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022” in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, led by ACS cancer surveillance researcher Angela Giaquinto, MSPH. Giaquinto and Rebecca Siegel, MPH, as well as their department lead Ahmedin Jemal, DVM, PhD, also produced the consumer-friendly companion, Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2022-2024. These reports provide detailed analyses of breast cancer occurrence and current information on known risk factors, early detection, and treatment.

Here's an overview of some key statistics from both reports.

New diagnoses of breast cancer continue slow increase in 2022.

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in the US, after nonmelanoma skin cancer. It mostly affects women age 50 and older, who develop about 83% of new breast cancer cases and represent 91% of deaths from breast cancer. Half of the women who die from breast cancer in the US are age 70 or older.

Men can get breast cancer, too, but this is much less common. In 2022, an estimated 287,850 women and 2,710 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer. An estimated 43,250 women and 530 men will die from the disease.

Breast cancer incidence rates have risen slowly in most of the past 40 years. During the most decade of data, 2010 through 2019, the rate increased by 0.5% a year. The increase is likely due at least in part to more women having excess body weight and the declining fertility rate of women in the US.

The total fertility rate of a population is the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime, and it’s been found to be related to the risk of developing breast cancer. Women who have not given birth to children or who gave birth to their first child after age 30 have a slightly higher overall risk for developing breast cancer later in life. Having many pregnancies and becoming pregnant before age 30 reduces a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.

Build Your Knowledge

See Understanding Cancer Research Terms. Get more out of ACS studies on epidemiology, statistics, genetics, and other complex topics with this glossary of research terms, explained in plain language for nonscientists.

The effect of weight and fertility rates seem to be limited to an increased risk of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (HR+)—the most common type of breast cancer and the largest driver of increasing incidence rates. HR+ tumors are more likely to be detected early through mammography compared to HR- tumors, and they have higher survival.

Most new breast cancer cases are diagnosed at a localized stage, meaning they have not spread outside of the breast. These early-stage cancers are most often found during breast cancer screening and typically have a high rate of survival because treatment is more effective at this stage.

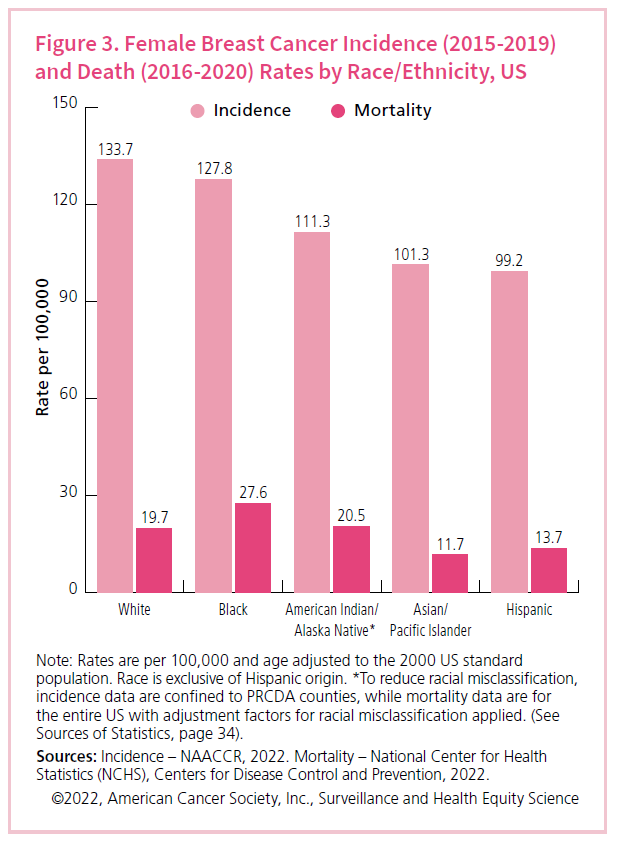

Black women still have a 4% lower incidence rate of breast cancer than White women but a 40% higher breast cancer death rate.

In this graphic, the breast cancer incidence rate (light pink bars) is highest in White women and lowest in Hispanic women. The breast cancer death-rate (dark pink bars) is highest in Black women, followed by American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) women, and lowest in Asian/Pacific Islander women. It's notable that Black and AIAN women both have a higher death rate than White women even though they both have a lower incidence rate for breast cancer than White women.

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death after lung cancer in women in the US overall, but it’s the leading cause of cancer death in Black and Hispanic women.

During 2016 through 2020, the breast cancer incidence rate was higher in Black women compared to White women in only 4 states: Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Virginia. In contrast, the breast cancer death rate was higher for Black women than White women in every state except Washington.

“Geographical disparities in breast cancer incidence and mortality are due to the differences in the prevalence of risk factors and access to screening and treatment. All of these are influenced by a woman’s socioeconomic status and her distance to medical services, as well as government policies in the state where she lives, such as whether it expanded Medicaid.” —Rebecca Siegel, MPH

Overall, the pace of the reduction in female breast cancer death rates is slower than it was during the 1990s and 2000s. Still, the 43% overall decline in mortality translates to 460,000 deaths avoided between 1989 and 2020. This decline is attributed to earlier detection through breast cancer screening and increased awareness of the disease as well as improvements in treatment.

The racial disparity in deaths from breast cancer has remained at 40% or higher for a decade.

- Black women younger than age 50 had a death rate that was twice as high as White women that age. Plus, Black women are more likely than White women to die of breast cancer at any age.

- AIAN women were 17% less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than White women but 4% more likely to die from the disease.

Part of the reason the breast cancer death rate is not dropping as fast as it has in previous years is because screening rates aren’t increasing and too few women are receiving timely and high-quality treatment after they’re diagnosed with breast cancer.

The study authors point out that “progress against breast cancer mortality could be accelerated by mitigating racial disparities through increased access to high-quality screening and treatment via nationwide Medicaid expansion and partnerships between community stakeholders, advocacy organizations, and health systems.”

“Coordinated and concerted efforts by policy makers, healthcare systems, and providers are needed to provide optimal breast cancer care to all populations and reduce breast health disparity and accelerate progress against the disease. These efforts include expansion of Medicaid in the 12 non-expansion states and increased investment for new early detection methods and treatments.”—Ahmedin Jemal, DVM, PhD, ACS senior vice president of Surveillance & Health Equity Science

Black women have the lowest survival for all subtypes of breast cancer.

In this graphic, the bars show the percentage of women who are still alive 5 years after a cancer diagnosis based on the cancer’s stage when they were diagnosed (listed along the bottom) and their ethnicity (shown by color). At each stage, Black women, who are represented by the light pink bars, have the lowest survival. Black women who develop breast cancer are less likely than any other race to be alive 5 years after their diagnosis, regardless of when their cancer’s when discovered or what type it is.

On January 1, 2022, more than 4 million women were living in the US with a history of invasive breast cancer. Some of them were cancer-free, while others still had evidence of cancer and may have been undergoing treatment.

- Black women have the lowest 5-year relative breast cancer survival rate compared to all other racial/ethnic groups for every stage of diagnosis and every breast cancer subtype.

- The largest disparities in 5-year relative survival are for regional and distant stage breast cancer. Only 78% of Black women are living at least 5 years after their diagnosis of regional stage breast cancer compared to 88% of White women. For distant stage, the gap is slightly larger – 21% versus 32%

- There is a 6% to 8% gap in 5-year survival between Black and White women for every breast cancer subtype.

Up to about 30% of breast cancers may be preventable with changes in lifestyle.

About 30% of breast cancer diagnoses are linked to risk factors that women may be able to change—such as excess body weight, physical inactivity, and alcohol intake.

Women can help lower their risk for developing breast cancer by being active, maintaining a healthy body weight, and limiting alcohol. They can also help lower their risk of death from breast cancer by talking with their doctor about how often to get a mammogram, sticking with that schedule, and promptly following up on any abnormal results. Following American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening can help women find breast cancer earlier, when treatments are more likely to be effective.

The advocate affiliate of the ACS, the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) continues to make efforts to close this persistent gap in screening.

“Lawmakers can and must do more to address the unequal burden of breast cancer among Black women, including increasing funding for the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), a program jointly funded by federal and state governments that helps improve access to lifesaving screenings for these cancers.” —Lisa A. Lacasse, ACS CAN president

- Helpful resources

- For researchers

All Facts & Figures Publications

Breast Cancer ACS Research Highlights

45 Minutes/Day of Physical Activity May Help Prevent Some Cancers

Expert Panel: Physical Activity Helps Prevent Cancer and May Help Cancer Survivors Live Longer

US States Vary in How Drinking Alcohol Affects Cancer Diagnoses and Deaths