What Is Thyroid Cancer?

Thyroid cancer is a type of cancer that starts in the thyroid gland. The thyroid makes hormones that help regulate your metabolism, heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature.

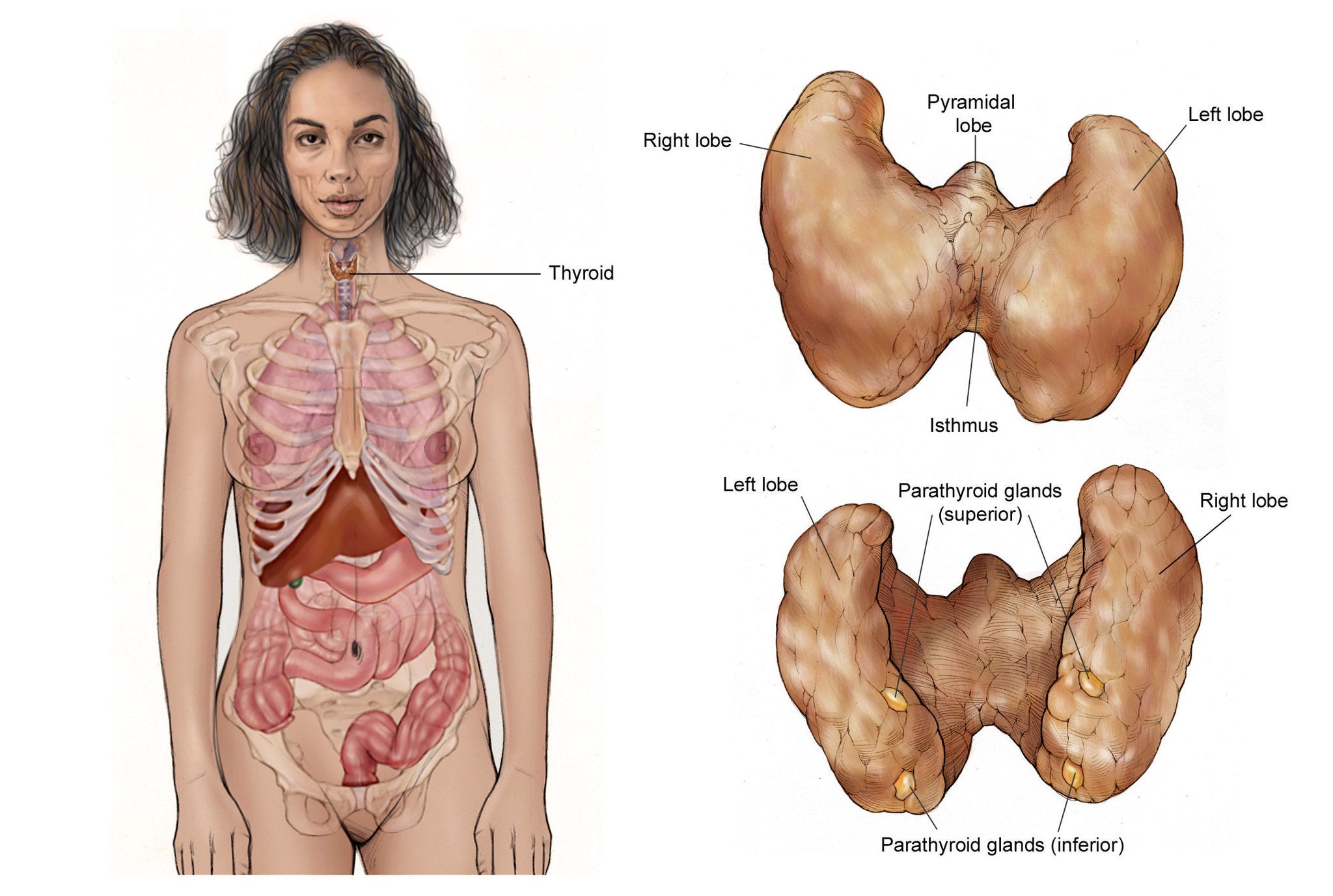

Where thyroid cancer starts

The thyroid gland is in the front part of the neck, below the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple). In most people, the thyroid can’t be seen or felt. It is shaped like a butterfly, with 2 lobes — the right lobe and the left lobe. These lobes are joined by a narrow piece of gland called the isthmus (see picture below).

© American Society for Clinical Oncology. Used with permission.

The thyroid makes hormones that help regulate your metabolism, heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature. The amount of thyroid hormone released by the thyroid is regulated by the pituitary gland at the base of your brain. This gland makes a substance called thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Having too much thyroid hormone (hyperthyroidism) can cause a fast or irregular heartbeat, trouble sleeping, nervousness, hunger, weight loss, and a feeling of being too warm.

Having too little hormone (hypothyroidism) causes you to slow down, feel tired, and gain weight.

The thyroid gland has 2 main types of cells:

- Follicular cells use iodine from the blood to make thyroid hormones. These hormones help regulate your metabolism.

- C cells (also called parafollicular cells) make calcitonin, a hormone that helps control how your body uses calcium.

Other, less common cells in the thyroid gland include immune system cells (lymphocytes) and supportive (stromal) cells.

Different types of thyroid cancer can develop from each kind of cell.

Many types of growths and tumors can develop in the thyroid gland. Most of these are benign (non-cancerous), but others are malignant (cancerous), which means they can spread into nearby tissues and to other parts of the body

Thyroid conditions that are usually benign

Changes in your thyroid gland’s size or shape can often be felt, or even seen, by you or your doctor. Most often, these changes are benign (not cancer).

Thyroid enlargement

An enlarged thyroid gland is sometimes called a goiter. Some goiters are diffuse, meaning that the whole gland is large. Other goiters are nodular, meaning that the gland is large and has one or more nodules (bumps) in it.

There are many reasons the thyroid gland might be larger than usual. Most of the time it isn’t from cancer.

Goiters (both diffuse and nodular) are usually caused by an imbalance in certain hormones. For example, not getting enough iodine in your diet can affect your hormone levels and cause a goiter.

Thyroid nodules

Lumps or bumps in the thyroid gland are called thyroid nodules. Most thyroid nodules are benign, but a small percentage are cancer. You can develop thyroid nodules at any age, but it happens most often in older adults.

Some nodules cause the body to make too much thyroid hormone, which can lead to hyperthyroidism. These nodules are almost always benign.

A small portion of adults have thyroid nodules that can be felt by a doctor. But many more people have nodules that are too small to feel. These might only be seen on a test such as an ultrasound.

Most thyroid nodules are cysts filled with fluid or with a stored form of thyroid hormone called colloid. Other nodules are solid, with very little fluid or colloid. Solid nodules are more likely to be cancer. Still, most solid nodules are not cancerous.

Some types of solid nodules (such as hyperplastic nodules and adenomas) have too many cells, but the cells are not cancer cells.

Benign thyroid nodules can sometimes just be watched closely, as long as they aren’t growing or causing symptoms. Others might need some form of treatment.

Types of thyroid cancer

The main types of thyroid cancer are:

- Differentiated (including papillary, follicular, and oncocytic carcinoma)

- Medullary

- Anaplastic

Differentiated thyroid cancers

Most thyroid cancers are differentiated cancers. The cells in these cancers look a lot like normal thyroid cells when seen in the lab. These cancers develop from thyroid follicular cells.

Papillary thyroid cancer

Papillary thyroid cancer (also called papillary carcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma) is the most common type. About 8 out of 10 thyroid cancers are papillary cancers.

These cancers tend to grow very slowly and usually develop in only one lobe of the thyroid gland. They sometimes spread to the lymph nodes in the neck. But even when this happens, they can often be treated successfully and are rarely fatal.

There are several subtypes (called variants) of papillary thyroid cancer:

- The follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer is the most common. It is treated the same way as the standard type of papillary cancer, and it tends to have the same good outlook (prognosis) when found early.

- Other variants of papillary carcinoma (including tall cell, columnar, insular, clear cell, trabecular, hobnail, and diffuse sclerosing) are not as common. They tend to grow and spread more quickly and might need more intensive treatment.

Follicular thyroid cancer

Follicular thyroid cancer (also called follicular carcinoma or follicular adenocarcinoma) is the next most common type, making up about 1 out of 10 thyroid cancers. (It is different from the follicular variant of papillary cancer, described above.)

This type of thyroid cancer is more common in countries where people don’t get enough iodine in their diet. These cancers usually do not spread to lymph nodes, but they can spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs or bones.

The outlook (prognosis) for follicular cancer is not quite as good as that of papillary cancer, although it is still very good in most cases.

Oncocytic carcinoma of the thyroid

About 3% of thyroid cancers are oncocytic carcinoma of the thyroid (previously called Hürthle (Hurthle) cell cancer). This type of thyroid cancer tends to be harder to find and to treat.

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC)

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC, also known as medullary thyroid carcinoma) accounts for less than 5% of all thyroid cancers. It develops from the C cells of the thyroid gland, which normally make calcitonin. (Calcitonin is a hormone that helps control the amount of calcium in blood.)

MTC can be harder to find and treat. Sometimes it can spread to the lymph nodes, lungs, or liver before a thyroid nodule is even discovered.

There are 2 types of MTC:

Sporadic MTC

Sporadic MTC accounts for about 3 out of 4 cases of MTC. It is not inherited (meaning it does not run in families). It occurs mostly in older adults and often affects only one thyroid lobe.

Familial MTC

Familial MTC is inherited (runs in families). It accounts for about 1 in 4 cases of MTC. It often develops during childhood or early adulthood and can spread early.

People with familial MTC usually have cancer in several areas of both lobes. Familial MTC can occur by itself, or it can be part of a syndrome that includes an increased risk of other types of tumors. This is described in more detail in Thyroid Cancer Risk Factors.

Anaplastic (undifferentiated) thyroid cancer

Anaplastic carcinoma (also called undifferentiated carcinoma) is rare. It makes up about 2% of all thyroid cancers. Most often, it is thought to develop from an existing papillary or follicular cancer.

Anaplastic cancer cells do not look very much like normal thyroid cells. This cancer often spreads quickly into the neck and to other parts of the body, and it can be hard to treat.

Less common thyroid cancers

Other rare cancers found in the thyroid include:

- Thyroid lymphoma

- Thyroid sarcoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the thyroid

- Other rare thyroid cancers

Parathyroid cancer

The parathyroids are 4 tiny glands behind, but attached to, the thyroid gland. Your parathyroid glands help regulate your body’s calcium levels. Cancers of the parathyroid glands are very rare.

Parathyroid cancers are often found when they cause high blood calcium levels. High blood calcium levels can make you feel tired, weak, and drowsy. They can also make you urinate (pee) a lot, causing dehydration.

Other symptoms of parathyroid cancer can include bone pain and fractures, pain from kidney stones, depression, and constipation.

The main treatment for most parathyroid cancers is surgery to remove the cancer. Sometimes, medicines are used to help control symptoms caused by high blood calcium levels. Parathyroid cancer tends to be harder to cure than thyroid cancer.

The rest of our information on thyroid cancer does not cover parathyroid cancer.

- Written by

- References

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

Asban A, Patel AJ, Reddy S, Wang T, Balentine CJ, Chen H. Chapter 68: Cancer of the Endocrine System. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Doroshow JH, Kastan MB, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa. Elsevier: 2020.

Fuleihan GE, Arnold A. Parathyroid carcinoma. UpToDate. 2024. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/parathyroid-carcinoma on February 6, 2024.

National Cancer Institute. Thyroid Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. 2023. Accessed at https://www.cancer.gov/types/thyroid/hp/thyroid-treatment-pdq on February 6, 2024.

Ross DS. Diagnostic approach to and treatment of thyroid nodules. UpToDate. 2024. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnostic-approach-to-and-treatment-of-thyroid-nodules on February 7, 2024.

Tuttle RM. Papillary thyroid cancer: Clinical features and prognosis. UpToDate. 2024. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/papillary-thyroid-cancer-clinical-features-and-prognosis on February 6, 2024.

Last Revised: August 23, 2024

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.