Your gift is 100% tax deductible.

Ovarian Cancer

If you have ovarian cancer or are close to someone who does, knowing what to expect can help you cope. Here you can find out all about ovarian cancer, including risk factors, symptoms, how it is found, and how it is treated.

About ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancers were previously believed to begin only in the ovaries, but recent evidence suggests that ovarian cancers may also start in cells in the fallopian tubes.

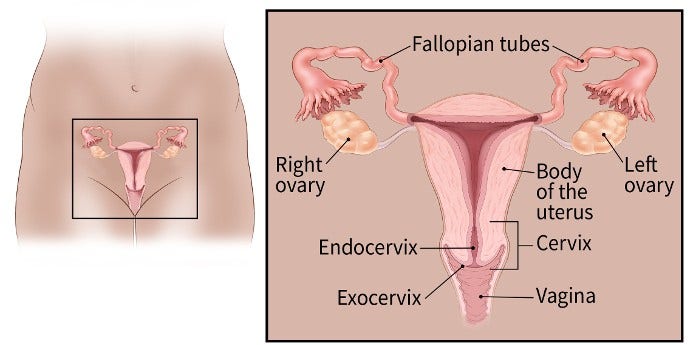

The ovaries

Ovaries are reproductive glands found only in females. One ovary is located on each side of the uterus. The ovaries produce eggs (ova) for reproduction. The eggs travel from the ovaries through the fallopian tubes into the uterus where the fertilized egg settles in and develops into a fetus. The ovaries are also the main source of the female hormones, estrogen and progesterone.

The ovaries are mainly made up of 3 kinds of cells. Each type can develop into a different type of tumor:

- Epithelial tumors start from epithelial cells that line the fallopian tubes and ovaries. Most ovarian tumors are epithelial cell tumors.

- Germ cell tumors start from the cells that produce the eggs (ova).

- Stromal tumors start from structural tissue cells that hold the ovary together and produce the female hormones, estrogen and progesterone.

Some of these tumors are benign (non-cancerous) and do not spread beyond the ovary. Malignant (cancerous) or borderline (low malignant potential) ovarian tumors can spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body and can be fatal.

Types of ovarian tumors and related conditions

Epithelial ovarian tumors may start in the epithelial cells that line the fallopian tubes and ovaries. These tumors can be benign (non-cancerous), borderline (low malignant potential), or malignant (cancerous).

Benign epithelial ovarian tumors

Benign epithelial ovarian tumors do not spread and usually do not lead to serious illness. There are several types of benign epithelial tumors including serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystadenomas, and Brenner tumors.

Borderline epithelial ovarian tumors

Some ovarian epithelial tumors don’t clearly appear to be cancerous and are called borderline epithelial ovarian tumors. These tumors are also known as tumors of low malignant potential (LMP tumors). The two most common types are serous borderline tumor (SBT) and mucinous borderline tumor (MBT). They are different from malignant epithelial ovarian cancers because they don’t grow into the ovarian stroma, which is the supporting tissue of the ovary. If they spread outside the ovary, for example, into the abdominal cavity (belly), they might grow on the lining of the abdomen but not into it.

Borderline tumors tend to affect younger women. These tumors grow slowly and are less life-threatening than most ovarian cancers.

Malignant epithelial ovarian tumors

About 85% to 90% of ovarian cancers are epithelial ovarian carcinomas. These are classified into 5 main types, based on genetic analysis and what the tumor cells look like under a microscope:

- High-grade serous carcinoma (This is the most common type.)

- Low-grade serous carcinoma

- Endometrioid carcinoma

- Clear cell carcinoma

- Mucinous carcinoma

Other less common types of malignant epithelial ovarian carcinoma include mesonephric-like carcinoma and carcinosarcoma.

Endometrioid ovarian cancer is given a grade based on how much the tumor cells look like normal tissue:

- Grade 1 epithelial ovarian carcinomas look more like normal tissue and tend to have a better prognosis (outlook).

- Grade 3 epithelial ovarian carcinomas look less like normal tissue and usually have a worse outlook.

Primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC) is a rare cancer closely related to epithelial ovarian cancer. At surgery and in the lab, it looks the same as an epithelial ovarian cancer that has spread through the abdomen.

Like ovarian cancer, PPC tends to spread along the surfaces of the pelvis and abdomen, so it is often difficult to tell exactly where the cancer first started. This type of cancer can occur in women who still have their ovaries, but it is of more concern for women who have had their ovaries removed to prevent ovarian cancer. This cancer does rarely occur in men.

Symptoms of PPC are like those of ovarian cancer, including abdominal pain or bloating, nausea, vomiting, indigestion, and a change in bowel habits. Also, like ovarian cancer, PPC may elevate the blood level of a tumor marker called CA-125.

Women with PPC usually get the same treatment as those with widespread ovarian cancer. This could include surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible (a process called debulking), followed by chemotherapy like that given for ovarian cancer. Its outlook is likely to be similar to widespread ovarian cancer.

Fallopian tube cancer is similar to epithelial ovarian cancer and often spreads to the ovary and peritoneum. It begins in the fallopian tube, which is the structure that carries an egg from the ovary to the uterus. Like PPC, fallopian tube cancer and ovarian cancer have similar symptoms. The treatment for fallopian tube cancer is similar to that for ovarian cancer, but the outlook (prognosis) may be slightly better if it is confined to the fallopian tube.

Germ cells usually form the eggs (ova) in females and the sperm in males. Most ovarian germ cell tumors are benign, but some are cancerous and may be life threatening. Less than 2% of ovarian cancers are germ cell tumors. Overall, they have a good outlook, with more than 9 out of 10 patients surviving at least 5 years after diagnosis. There are several subtypes of germ cell tumors. Germ cell tumors can also be a mix of more than a single subtype.

The most common germ cell tumors are:

- Teratomas

- Dysgerminoma

- Yolk sac tumor, also called endodermal sinus tumor

- Mixed germ cell tumors

Teratoma

Teratomas are germ cell tumors contain each of the 3 layers of a developing embryo:

- Endoderm (innermost layer)

- Mesoderm (middle layer)

- Ectoderm (outer layer)

Teratomas can be benign (mature teratomas) or cancerous (immature teratomas).

Mature teratomas are the most common ovarian germ cell tumors. They are usually benign and affect people of reproductive age (teens through 40s). These tumors can be solid or, more often, fluid-filled. Fluid-filled teratomas are called dermoid cysts because their lining resembles skin and may contain bone, hair, teeth, or other tissue. They are treated with surgery to remove the tumor.

Immature teratomas are rare cancers that usually occur in girls and young women younger than 18. They contain cells that look like embryonic or fetal tissues, such as connective tissue, respiratory passages, and brain. Treatment depends on the grade of the teratoma (how immature they appear).

- Grade 1 immature teratomas (which appear more mature) that haven’t spread outside the ovary are treated by removing the ovary.

- Grade 2 or 3 immature teratomas (which appear very immature) and those that have spread may need chemotherapy in addition to surgery.

Dysgerminoma

While this type of cancer is rare, it is the most common ovarian germ cell cancer. It usually affects women in their teens and twenties. Dysgerminomas are malignant (cancerous) and can grow rapidly in certain cases. If the cancer is limited to the ovary, it is removed with surgery. If it has spread or comes back, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and/or additional surgery are often effective in controlling or curing the cancer.

Yolk sac tumor (Endodermal sinus tumor)

Yolk sac tumors typically affect girls and young women. They generally grow and spread rapidly but are usually sensitive to chemotherapy. Yolk sac tumors tend to cause an elevated blood level of a tumor marker called AFP (alpha fetoprotein).

Mixed germ cell tumors

Mixed germ cell tumors are made up of two or more different ovarian germ cell tumors, most often a combination of dysgerminoma and yolk sac tumor. They generally grow and spread rapidly but are usually sensitive to chemotherapy.

Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors (SCSTs) are a group of tumors that originate either from the sex cord or stromal cells:

- Sex cord cells are a type of epithelial cells that eventually develop into ovaries (in females) and testes (in males).

- Stromal cells form the connective tissue that gives the ovaries structure.

SCSTs are less common than epithelial ovarian cancer or ovarian germ cell tumors. They can be either benign or malignant. Malignant SCSTs are often found at an early stage and have a good outlook, with more than 75% of patients surviving long-term.

SCSTs are classified into 3 main categories: pure sex cord tumors, pure stromal tumors, and mixed sex cord-stromal tumors. Within each category, there are sub-types of tumors. The main subtypes are:

Pure sex cord tumors

- Granulosa cell tumor (most common type of low malignant SCST)

- Sertoli cell tumor

Pure stromal tumors

- Fibroma (most common type of benign SCST)

- Thecoma (usually a benign SCST)

Mixed sex cord-stromal tumors

- Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor

An ovarian cyst is a collection of fluid inside an ovary. Most ovarian cysts are functional cysts that occur as a normal part of the process of ovulation (egg release) and usually go away within a few months without any treatment.

If you develop a cyst, your doctor may want to check it again after your next menstrual cycle (period) to see if it has gotten smaller. The doctor may want to do more tests if the cyst:

- Occurs in someone who isn't ovulating (like a woman after menopause or a girl who hasn't started her periods)

- Is large

- Does not go away in a few months.

Even though most of these cysts are benign (not cancer), a small number of them could be cancer. Sometimes the only way to know for sure is to take the cyst out with surgery. Cysts that appear to be benign (based on how they look on imaging tests) can be observed (with repeated physical exams and imaging tests), or removed with surgery.

Quick guides

- Written by

- References

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2025.

Cannistra SA, Gershenson DM, Recht A. Ch 76 - Ovarian cancer, fallopian tube carcinoma, and peritoneal carcinoma. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015.

DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT. Germ cell, stromal and other ovarian tumors. In: Clinical Gynecologic Oncology, 7th, Mosby-Elsevier, 2007. p.381

Fleming GF, Seidman JD, Yemelyanova A and Lengyel E. (2017). Chapter 23: Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. In D. S. Chi, A. Berchuck, D. S. Dizon, & C. M. Yashar (Authors), Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology (7th ed). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health.

Lim D, Oliva E. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumours: an update in recent molecular advances. Pathology 2018; 50:178.

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Female genital tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020.

Last Revised: August 8, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

This information is possible thanks to people like you.

We depend on donations to keep our cancer information available for the people who need it most.